Table of Contents

About This Issue

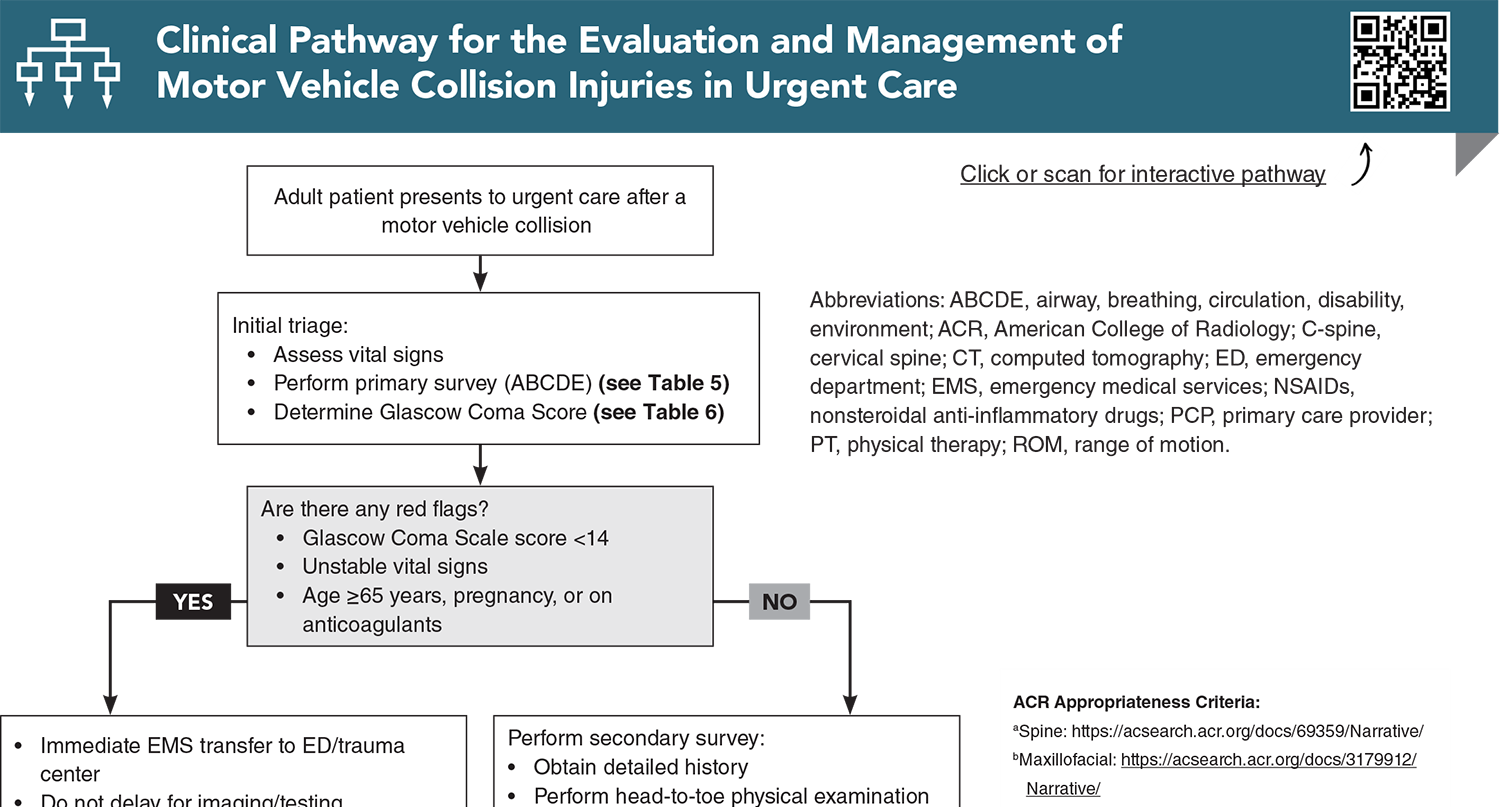

Motor vehicle collision (MVC) injuries are a common presentation in urgent care. Although many post-MVC patients appear ambulatory and stable, significant or life-threatening injuries may still be present—particularly with high-risk mechanisms, older age, pregnancy, or anticoagulant use. The article emphasizes the importance of mechanism-of-injury assessment, standardized trauma evaluation (primary survey, Glascow Coma Score), judicious use of validated clinical decision rules, and clear thresholds for imaging and emergency department referral. Practical guidance is provided for common MVC-related injuries involving the head, cervical spine, thorax, abdomen, pelvis, and extremities, with a focus on avoiding missed injuries and delays in definitive care. In this issue, you will learn:

How to apply a systemic triage and evaluation strategy for post-MVC patients (adult and pediatric) presenting to urgent care, even when symptoms are delayed or occult;

Why the mechanism of injury is often more predictive of serious trauma than the patient’s initial presentation;

When and how to use validated decision rules, such as the Canadian CT Head Rule, Canadian C-Spine Rule, and the Ottawa Ankle or Knee Rule), to guide imaging and referral decisions; and

Evidence-based management strategies for common MVC-related injuries.

CODING & CHARTING: Documenting details of the accident and the patient’s multiple subtle injuries are paramount when coding for a patient presentation after an MVC. Learn more in our monthly coding column.

- About This Issue

- Abstract

- Case Presentations

- Introduction

- Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Differential Diagnosis

- Urgent Care Evaluation

- Triage and Stabilization

- History

- Physical Examination

- Diagnostic Studies

- Laboratory and Bedside Studies

- Plain Radiography

- Advanced Imaging

- Treatment

- Head Injury

- Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

- Postconcussion Syndrome

- Moderate Traumatic Brain Injury

- Cervical Spine Injury

- Whiplash

- Intervertebral Disc Derangement

- Spinal Cord Injury

- Chest and Abdominal Trauma

- Thoracolumbar Spine Injury

- Pelvis and Hip Trauma

- Upper and Lower Extremity Injuries

- Contusions, Sprains, and Strains

- Fractures and Dislocations

- Crush Injuries and Compartment Syndrome

- Psychological Effects

- Pain Management

- Special Populations

- Older Patients

- Pregnant Patients

- Patients Taking Anticoagulants and Antiplatelet Agents

- Controversies and Cutting Edge

- Disposition

- Summary

- Time- And Cost-Effective Strategies

- 5 Things That Will Change Your Practice

- Risk Management Pitfalls for the Evaluation and Management of Motor Vehicle Collision Injuries in Urgent Care

- KidBits: Urgent Care Evaluation and Management of Motor Vehicle Collisions Injuries in Pediatric Patients

- Urgent Care Evaluation

- Specific Injuries and Their Management

- Head Trauma

- Abdominal Trauma

- Cervical Spine Injury

- Other Considerations

- Disposition

- Key Points

- Clinical Pathway for the Urgent Care Evaluation and Management of Motor Vehicle Collision Injuries in Pediatric Patients

- References

- Case Conclusions

- Coding & Charting: What You Need to Know

- Coding Challenge: A Motor Vehicle Collision Presentation in Urgent Care

- Clinical Pathway for the Evaluation and Management of Motor Vehicle Collision Injuries in Urgent Care

- References

Abstract

Motor vehicle collision injuries are frequently seen in urgent care and may be associated with significant patient morbidity and clinician diagnostic uncertainty. Effective evaluation begins with a thorough history and physical examination, with particular attention to the mechanism of injury. In most cases, diagnosis and management are guided by validated clinical decision rules and the judicious use of diagnostic imaging. While many post–motor vehicle collision injuries are minor, urgent care clinicians must be able to identify potentially serious or life-threatening conditions, recognize high-risk populations, and facilitate timely referral to a higher-acuity facility when necessary. This review outlines an evidence-based approach to the evaluation and management of motor vehicle collision-related injuries in the urgent care setting.

Case Presentations

- He states he was the unrestrained driver of a dump truck that went through a guardrail and fell 30 feet to the ground.

- He was initially transported to the regional trauma center via EMS and was treated and released.

- He complains of persistent headaches with blurry vision, thoracolumbar spine pain, and right lower extremity swelling with difficulty bearing weight. He reports that his imaging studies at the trauma center were “normal.”

- You have a sense of reassurance that he has been previously evaluated at a Level 1 trauma center, but you wonder how to manage his complaints…

- She reports that she was wearing a seat belt and was seated in the front passenger seat when another vehicle, traveling approximately 40 to 45 mph, struck the passenger side of her vehicle while it was crossing an intersection. She declined EMS transport at the scene.

- She complains of right-sided chest wall pain as well as right hip pain with difficulty bearing weight.

- She denies headache, neck pain, nausea, vomiting, and shortness of breath.

- She is alert and oriented. Her vital signs are: heart rate, 90 beats/min; blood pressure, 102/80 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 96% on room air. She has a past medical history of atrial fibrillation managed with apixaban.

- As you complete the remainder of the examination, you consider how you will proceed with her evaluation and management…

- He reports that he was the restrained driver of a car that was rear-ended by another car while he was stopped at a stoplight. The other driver claimed he was driving 25 mph and was braking when he struck the patient’s car.

- He had no pain immediately after the collision but developed neck and upper back discomfort and stiffness the morning after the incident. He denies any upper or lower extremity numbness, paresthesia, or weakness.

- He presents to urgent care at the request of his lawyer for proof of causation, documentation of the seriousness of his injuries, and evaluation for hidden injuries. You wonder how to manage this case…

How would you manage these patients? Subscribe for evidence-based best practices and to discover the outcomes.

Clinical Pathway for the Evaluation and Management of Motor Vehicle Collision Injuries in Urgent Care

Subscribe to access the complete Clinical Pathway to guide your clinical decision making.

Buy this issue and

CME test to get 4 CME credits.

Key References

Following are the most informative references cited in this paper, as determined by the authors.

7. * Lupton JR, Davis-O’Reilly C, Jungbauer RM, et al. Mechanism of injury and special considerations as predictive of serious injury: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2022;29(9):1106-1117. (Systematic review) DOI: 10.1111/acem.14489

48. * American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury, Valente JH, Anderson JD, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with mild traumatic brain injury: approved by ACEP board of directors, February 1, 2023 clinical policy endorsed by the Emergency Nurses Association (April 5, 2023). Ann Emerg Med. 2023;81(5):e63-e105. (Review) DOI:

53. * Michaleff ZA, Maher CG, Verhagen AP, et al. Accuracy of the Canadian C-spine rule and NEXUS to screen for clinically important cervical spine injury in patients following blunt trauma: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2012;184(16):E867-E876. (Systematic review; 15 studies) DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.120675

71. * Nishimura E, Finger A, Harris M, et al. One-view chest radiograph for initial management of most ambulatory patients with rib pain. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(1):144-150. (Retrospective cohort study; 1791 patients) DOI: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.01.200276

80. * Velmahos GC, Tatevossian R, Demetriades D. The “seat belt mark” sign: a call for increased vigilance among physicians treating victims of motor vehicle accidents. Am Surg. 2022;65(2):181-185. (Prospective study; 650 patients)

96. * Haj-Mirzaian A, Eng J, Khorasani R, et al. Use of advanced imaging for radiographically occult hip fracture in elderly patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology. 2020;296(3):521-531. (Systematic review and meta-analysis; 2992 patients) DOI: 10.1148/radiol.2020192167

Hsu JR, Mir H, Wally MK, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for pain management in acute musculoskeletal injury. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33(5):e158-e182. (Practice guideline)

116. *Qaseem A, McLean RM, O’Gurek D, et al. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic management of acute pain from non-low back, musculoskeletal injuries in adults: a clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians and American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):739-748. (Practice guideline) DOI: 10.7326/M19-3602

126. *American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Best practices guidelines in geriatric trauma management. 2023. Accessed December 15, 2025. (Practice guidelines)

Subscribe to get the full list of 147 references and see how the authors distilled all of the evidence into a concise, clinically relevant, practical resource.

Keywords: motor vehicle collision, mechanism of injury, Glascow Coma Score, primary survey, secondary survey, Ottawa Knee Rule, Ottawa Ankle Rule, Canadian C-Spine Rule, Canadian CT Head Rule, mild traumatic brain injury, concussion, postconcussive syndrome, moderate traumatic brain injury, Canadian CT Head Rule, central cord syndrome, fracture, Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) Guidelines, ABCDE algorithm, National Emergency X-ray Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) Rule, whiplash, whiplash-associated disorder, range of motion, intervertebral disc derangement, central cord syndrome, chest wall injury, chest contusions, pneumothorax, thoracolumbar spine injury, open fracture, crush injury, compartment syndrome, post-traumatic stress disorder, computed tomography, plain radiography, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)