Table of Contents

About This Issue

Diagnostic testing is essential in the urgent care setting, particularly point-of-care tests that enable timely diagnosis and treatment of common respiratory tract and genitourinary infections. Clinicians must understand the limitations of the testing platforms used in their clinic and apply diagnostic stewardship and clinical gestalt. Effective use of laboratory testing enables clinicians to make appropriate diagnostic decisions, leading to knowledgeable medical decision making and patient satisfaction. In this issue, you will learn:

The advantages and disadvantages of various types of diagnostic tests available to the urgent care clinician to evaluate respiratory and genitourinary infections;

How to develop a diagnostic and treatment plan for common upper respiratory infections and genitourinary complaints based on results from laboratory testing; and

Common pearls and pitfalls of current diagnostic methodologies.

CODING & CHARTING: Choosing and documenting laboratory testing for a respiratory tract or genitourinary infection ensures appropriate diagnosis, treatment, and reimbursement. Learn more in our monthly coding column.

- About This Issue

- Abstract

- Case Presentations

- Introduction

- Select Abbreviations

- Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Respiratory Tract Infections

- Genitourinary Conditions

- Differential Diagnosis

- Respiratory Tract Infections

- Genitourinary Conditions

- Urgent Care Evaluation

- History

- Respiratory Tract Infections

- Genitourinary Conditions

- Physical Examination

- Respiratory Tract Infections

- Genitourinary Conditions

- Diagnostic Studies

- Characteristics of Diagnostic Tests

- CLIA Certificates and Provider Performed Microscopy

- Direct Detection Versus Serology Testing

- Diagnostic Test Utilization

- Diagnostic Tests for Respiratory Tract Infections

- Streptococcal Pharyngitis

- Influenza and COVID-19

- Influenza Antigen Test

- COVID-19 Antigen Test

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae

- Diagnostic Tests for Urinary Tract Infections

- Diagnostic Tests for Vaginitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections

- Multiplex Testing

- Treatment

- Respiratory Tract Infections

- Influenza

- COVID-19

- Streptococcal Pharyngitis

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae

- Genitourinary Infections

- Vaginitis

- Gonorrhea and Chlamydia

- Mycoplasma genitalium

- Disposition

- Special Populations

- High-Risk Patients

- Cross-reactivity With Rheumatological Conditions

- Age-Dependent Testing

- Controversies and Cutting Edge

- Molecular Testing Versus Antigen Testing

- In-House Molecular Testing

- Management of Bacterial Vaginosis

- Molecular Testing Detection of Resistance Patterns

- Host-Based Diagnostic Testing

- Syndromic Multiplex Testing for Antibiotic Stewardship

- Nonlaboratory Diagnostics Utilizing Artificial Intelligence

- Summary

- 5 Things That Will Change Your Practice

- Risk Management Pitfalls for Laboratory Testing in Urgent Care

- Case Conclusions

- Time- and Cost-Effective Strategies

- Coding & Charting: What You Need to Know

- Determining the Level of Service

- Number and Complexity of Problems Addressed

- Complexity of Data

- Risk of Patient Management

- Documentation Tips

- Coding Challenge

- Clinical Pathways

- Clinical Pathway for the Laboratory Evaluation of Pharyngitis in Urgent Care

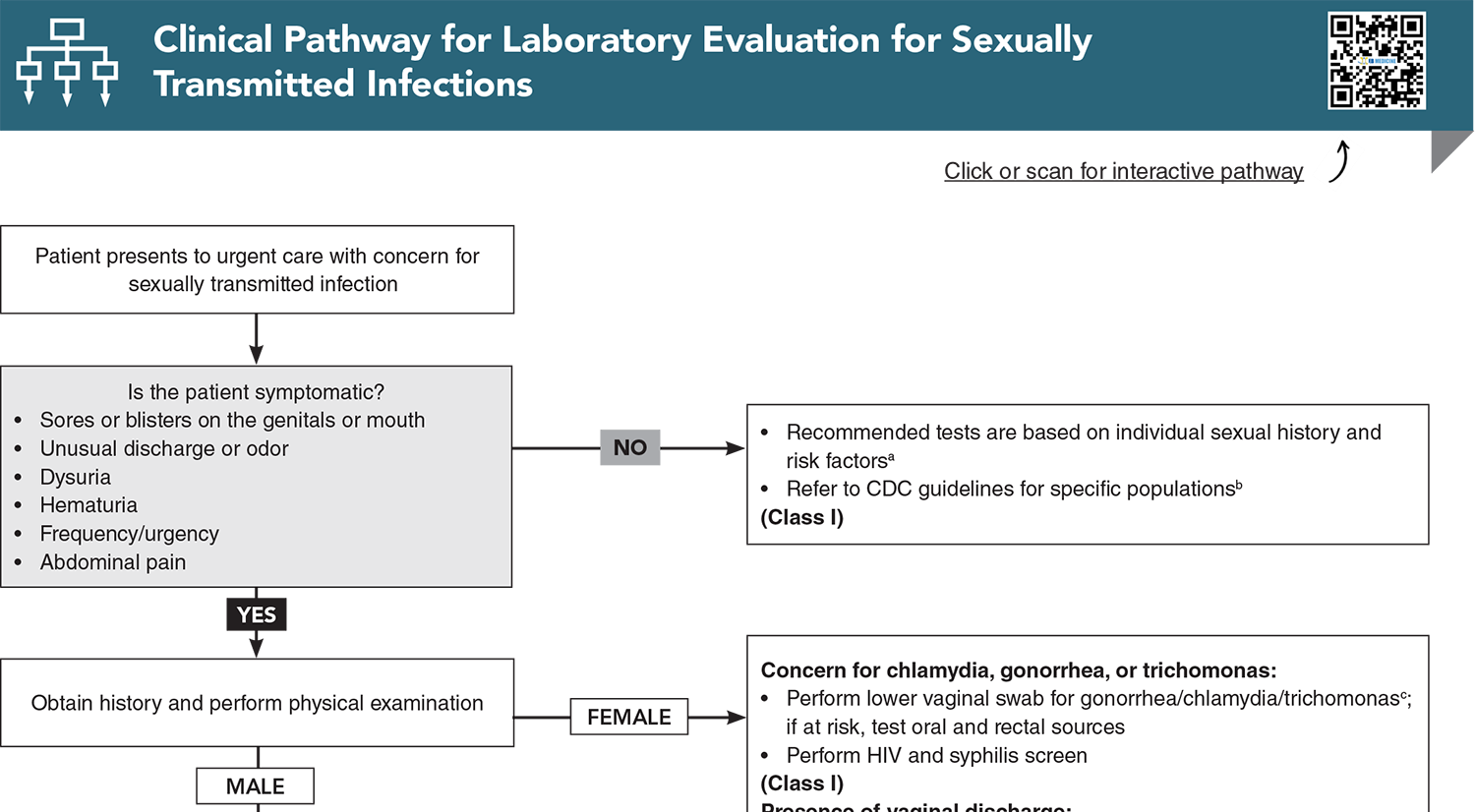

- Clinical Pathway for Laboratory Evaluation for Sexually Transmitted Infections

- Clinical Pathway for the Laboratory Evaluation and Management of COVID-19

- Clinical Pathway for the Laboratory Evaluation and Management of Influenza

- References

Abstract

Patients presenting to urgent care settings expect prompt diagnosis, treatment, and resolution of their symptoms. In order to provide high-quality, evidence-based care, urgent care clinicians must be familiar with currently available diagnostic tests and understand when to order or withhold those tests. This issue reviews diagnostic approaches used to evaluate respiratory and genitourinary complaints, including available testing modalities, their clinical utility and limitations, and practical recommendations for management. Key clinical pearls and common pitfalls are highlighted to support efficient, accurate diagnosis, and appropriate treatment decisions.

Case Presentations

- The physical examination is significant for tonsillar exudates and bilateral tender anterior cervical lymph nodes.

- An in-office rapid strep antigen test is negative.

- The patient’s mother asks you to prescribe an antibiotic for “strep throat.”

- Are empiric antibiotics the appropriate management choice for this patient? Is additional testing needed and if so, which tests?

- She states that she is certain this is "another UTI" and requests antibiotics.

- A review of her chart indicates that she has had 4 previous visits to urgent care in the past 6 months, with no growth indicated on urine culture at 2 of those visits.

- She reports that she is sexually active with her partner of 6 months. She says it is a monogamous relationship but notes that the urinary tract infections seemed to start around the same time she became sexually active with this partner.

- She has been taking over-the-counter phenazopyridine for symptom relief.

- A urine pregnancy test is negative. The patient declined a pelvic examination because she is convinced this is a urinary tract infection.

- Is a urinalysis helpful in the initial diagnostic workup for this patient? Is a urine culture needed? Is any additional testing indicated?

- She presented to your clinic 2 days ago for vaginal discharge. The clinician who saw her had the patient self-swab for a molecular vaginitis and STI panels.

- Her results are negative for chlamydia, gonorrhea, Trichomonas, Atopobium, Megasphaera, bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria, and Candida glabrata and Candida krusei. She has low positive results for Gardnerella vaginalis, Candida albicans, and Ureaplasma hominis.

- Should you treat for Gardnerella, Candida, and Ureaplasma? How do you distinguish normal flora from pathogen? Do the patient’s history or physical examination alter your treatment plan?

- He states that his 5-year-old son was seen by the pediatrician yesterday and diagnosed with “walking pneumonia.” He requests a "pneumonia test” for himself.

- He reports a runny nose, low-grade fever, chest congestion, and cough for the past 2 days.

- He does not appear to be in any acute distress, and there are no adventitious lung sounds.

- What test(s) for atypical pneumonia, if any, should be performed? Are empiric antibiotics without testing appropriate?

How would you manage these patients? Subscribe for evidence-based best practices and to discover the outcomes.

Clinical Pathway for Managing Patients Presenting with Acute Diarrhea in Urgent Care

Subscribe to access the complete Clinical Pathway to guide your clinical decision making.

Buy this issue and

CME test to get 4 CME credits.

Key References

Following are the most informative references cited in this paper, as determined by the authors.

26. * US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Clinical laboratory improvement amendments (CLIA). Updated July 10, 2025. Accessed October 10, 2025. (Regulatory overview)

29. * Sha BE, Chen HY, Wang QJ, et al. Utility of Amsel criteria, Nugent score, and quantitative PCR for Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, and Lactobacillus spp. for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(9):4607-4612. (Observational diagnostic study; 96 patients) DOI: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4607-4612.2005

30. * US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical guidance for group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Updated March 1, 2024. Accessed October 15, 2025. (Clinical practice guidelines)

39. * Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(10):e86-102. (Clinical practice guideline) DOI: 10.1093/cid/cis629

53. * Mulholland S, Gavranich JB, Gillies MB, et al. Antibiotics for community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections secondary to Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(9):CD004875. (Cochrane systematic review; 12 studies; 1529 patients) DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004875.pub4

56. * Trautner BW, Cortes-Penfield N, Gupta K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA): 2025 guideline on management and treatment of complicated urinary tract infections: executive summary. 2025. (Clinical practice guidelines)

75. * Something J, Smithers G, Park I. A review of genital Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma infections for the urgent care clinician. J Urgent Care Med. 2024;18(8):13-19. (Review)

93. * Spinks A, Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB. Antibiotics for treatment of sore throat in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;12(12):CD000023. (Cochrane systematic review; 19 studies; 15,337 cases of sore throat) DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000023.pub5

Subscribe to get the full list of 105 references and see how the authors distilled all of the evidence into a concise, clinically relevant, practical resource.

Keywords: diagnostic testing, Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments, point-of-care testing, respiratory tract infection, adenovirus, rhinovirus, influenza, coronavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, urinary tract infections, sexually transmitted infections, vaginitis, bacteria, chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, herpes simplex virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), syphilis, cystitis, urethritis, pathogen, Provider Performed Microscopy, CLIA-waived test, CLIA-moderate test, serology testing, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), direct detection, culture, molecular test, antigen test, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, streptococcal pharyngitis, group A streptococcus, pneumonia, COVID-19, Infectious Diseases Society of America, rapid strep testing, strep rapid diagnostic testing, multiplex testing, nucleic acid amplification test, wet prep, rapid influenza diagnostic test, false positive, false negative, pretest probability, urine culture, specimen collection, vaginal swab, antiviral therapy, antibiotics, resistance testing, test of cure