Table of Contents

About This Issue

While established guidelines exist, wide variation persists in emergency department management of febrile seizures. Febrile seizures are generally benign in nature, but they can cause caregivers significant stress and anxiety, and require thoughtful counseling for caregivers. This issue discusses the presentation, diagnosis, management, and prognosis of simple febrile seizures and complex febrile seizures in children. Anticipatory guidance for families and disposition considerations are also provided. In this issue, you will learn:

Features that differentiate simple febrile seizures from complex febrile seizures

Factors that increase the risk for febrile seizure

Serious causes of fever and seizure that need to be excluded, including an intracranial pathology such as bleeding or space-occupying lesion, central nervous system infections such as meningitis and encephalitis, and trauma

Recommendations for prehospital care for seizing children

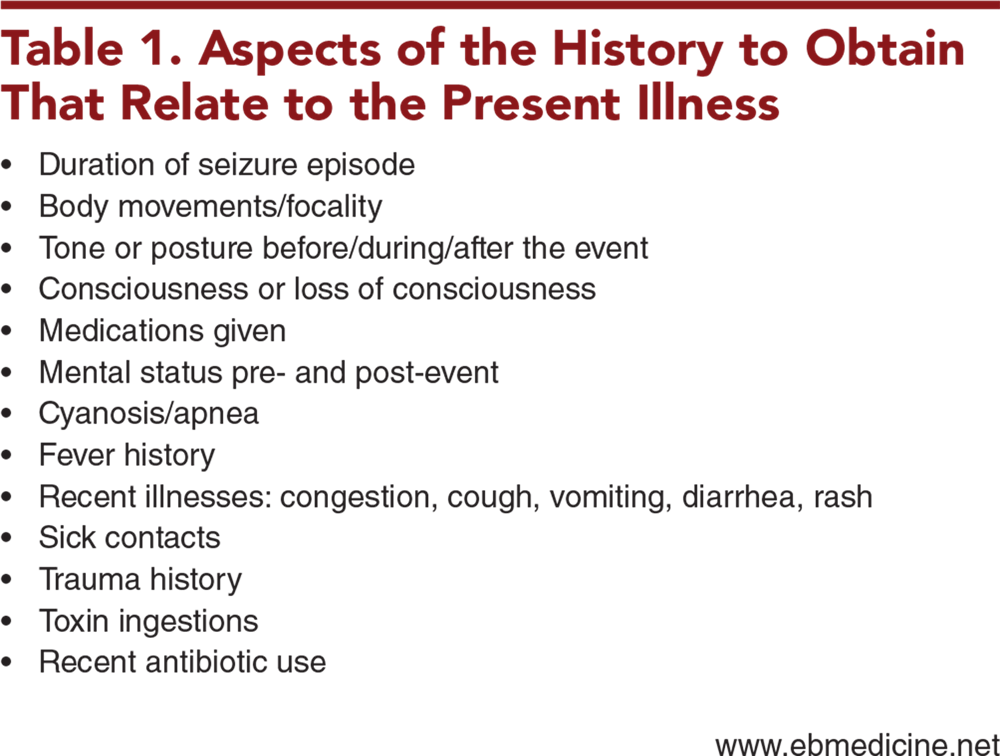

Aspects of the history to obtain that relate to the present illness, as well as past medical history to obtain

When laboratory studies, head imaging, lumbar puncture, or electroencephalography are indicated

Recommendations for treatment of febrile seizures including administration of antipyretics, benzodiazepines, antiseizure medications, and antimicrobials

Special considerations for children with developmental or intellectual delays and those with immunosuppressive conditions

Aspects to consider when deciding which patients should be admitted

Anticipatory guidance that should be provided to caregivers upon discharge

- About This Issue

- Abstract

- Case Presentations

- Introduction

- Definitions

- Febrile Seizures

- Febrile Status Epilepticus

- Critical Appraisal of the Literature

- Pathophysiology

- Differential Diagnosis

- Meningitis

- Simple Febrile Seizures

- Complex Febrile Seizures

- Encephalitis

- Intracranial Abnormalities

- Metabolic Changes

- Toxic Ingestions

- Prehospital Care

- Emergency Department Evaluation

- Diagnostic Studies

- Laboratory Studies

- Head Imaging

- Lumbar Puncture

- Electroencephalography

- Treatment

- Antipyretics

- Benzodiazepines

- Antiseizure Medications

- Treating the Cause of Fever

- Special Considerations

- Controversies

- Disposition

- Admission

- Anticipatory Guidance

- Risk for Febrile Seizure Recurrence

- Risk for Epilepsy

- 5 Things That Will Change Your Practice

- Risk Management Pitfalls in Managing Patients With Febrile Seizures in the Emergency Department

- Summary

- Case Conclusions

- Time- and Cost-Effective Strategies

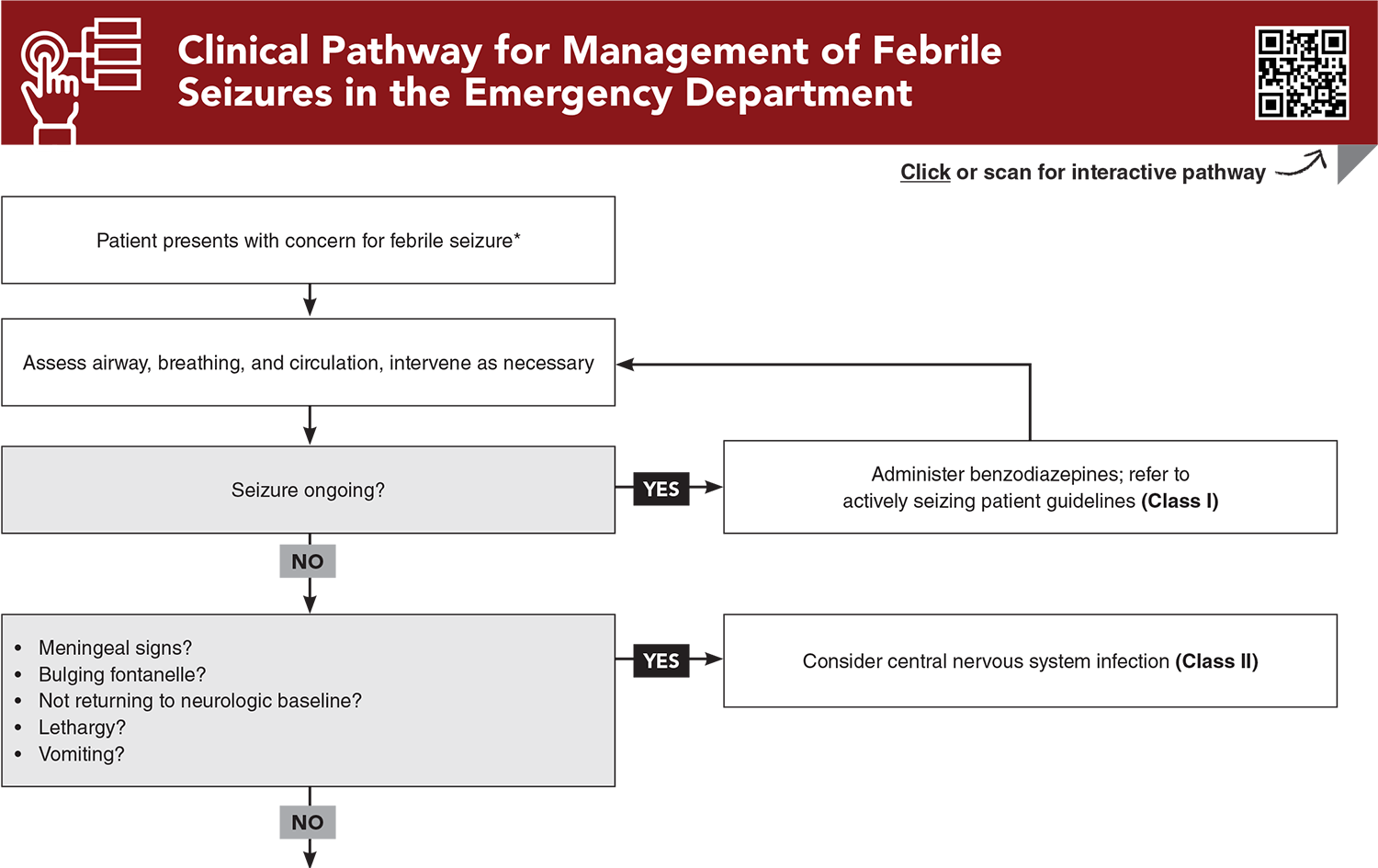

- Clinical Pathway for Management of Febrile Seizures in the Emergency Department

- Tables

- References

Abstract

Febrile seizures are a common presentation to emergency departments. While established guidelines exist, variation in the management and treatment of febrile seizures persists across emergency departments. This issue reviews the definition of pediatric febrile seizure and discusses the presentation, differential diagnosis, management, and prognosis. Anticipatory guidance for families and disposition considerations are also provided.

Case Presentations

- The girl’s mother explains both events were approximately 3 minutes in length and consisted of generalized full-body shaking that resolved spontaneously. She tells you the girl is fully vaccinated, with a history of a prior febrile seizure. The girl’s measured maximum temperature at home was 101.3°F.

- The girl’s vital signs are: temperature, 39.1°C; heart rate, 140 beats/min; blood pressure, 80/50 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 30 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 100%. On examination, the child is well-appearing and at baseline neurologically. Her mucous membranes are moist, and she has normal capillary refill. She has had a history of loose watery stools and 3 days of intermittent fevers, responsive to acetaminophen and ibuprofen. She has normal urinary output.

- What type of workup is indicated in the ED? What guidance should you provide to the family?

- The boy’s parents tell you that today is his third day of fever >101.3°F at home, and that he has had decreased oral intake. He has been on antibiotics for acute otitis media for the last 3 days. They also tell you the infant was born at full term and that he is unvaccinated.

- The boy’s vital signs are: temperature, 40°C; heart rate, 180 beats/min; blood pressure, 84/55 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 35 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 98%. The boy is sleeping in his father’s arms. The parents tell you he has been less active than usual. The infant is minimally arousable on examination and does not appear to have focal neurologic deficits. His capillary refill is 2 seconds. The examination is otherwise without obvious signs of infection. While in the ED, the boy vomits twice after trying to drink oral rehydration solution.

- The patient’s unvaccinated status and current antibiotic use increase his risk for serious infection. Which types of infection do you want to exclude in this patient?

- Upon arrival to the ED, the seizure activity has stopped. The boy is looking for his father and is now back to baseline. The boy’s vital signs are: temperature, 38.3°C; heart rate, 130 beats/min; blood pressure, 100/65 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 25 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 100%. The patient is observed in the ED for several hours and remains at baseline aside from moderate congestion. A respiratory viral panel is positive for respiratory syncytial virus. He has been tolerating oral intake and does not have any respiratory distress.

- The boy’s temperature has improved after antipyretic treatment, and his family is preparing for discharge.

- The patient’s family members are asking about starting medication to decrease future seizures. What type of prognosis for seizures does this patient have? How should you counsel the family?

How would you manage these patients? Subscribe for evidence-based best practices and to discover the outcomes.

Clinical Pathway for Managing Patients Presenting with Acute Diarrhea in Urgent Care

Subscribe to access the complete Clinical Pathway to guide your clinical decision making.

Tables

Subscribe for full access to all Tables and Figures.

Buy this issue and

CME test to get 4 CME credits.

Key References

Following are the most informative references cited in this paper, as determined by the authors.

7. * Subcommittee on Febrile Seizures. Febrile seizures: guideline for the neurodiagnostic evaluation of the child with a simple febrile seizure. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):389-394. (Guidelines) DOI: 10.1542/peds.2010-3318

8. * Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH. Predictors of epilepsy in children who have experienced febrile seizures. N Engl J Med. 1976;295(19):1029-1033. (Prospective; 1706 patients) DOI: 10.1056/NEJM197611042951901

16. * Trainor JL, Hampers LC, Krug SE, et al. Children with first-time simple febrile seizures are at low risk of serious bacterial illness. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(8):781-787. (Retrospective cohort; 455 patients) DOI: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb00207.x

20. * Green SM, Rothrock SG, Clem KJ, et al. Can seizures be the sole manifestation of meningitis in febrile children? Pediatrics. 1993;92(4):527-534. (Retrospective cohort; 503 patients) DOI: 10.1542/peds.92.4.527

21. * Kimia AA, Capraro AJ, Hummel D, et al. Utility of lumbar puncture for first simple febrile seizure among children 6 to 18 months of age. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):6-12. (Retrospective cohort; 704 cases) DOI: 10.1542/peds.2007-3424

24. * Kimia A, Ben-Joseph EP, Rudloe T, et al. Yield of lumbar puncture among children who present with their first complex febrile seizure. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):62-69. (Retrospective cohort; 526 patients) DOI: 10.1542/peds.2009-2741

27. * Offringa M, Beishuizen A, Derksen-Lubsen G, et al. Seizures and fever: can we rule out meningitis on clinical grounds alone? Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1992;31(9):514-522. (Case-control; 309 patients) DOI: 10.1177/000992289203100901

33. * Jaffe M, Bar-Joseph G, Tirosh E. Fever and convulsions--indications for laboratory investigations. Pediatrics. 1981;67(5):729-731. (Retrospective; 562 children) DOI: 10.1542/peds.67.5.729

51. * Rosenbloom E, Finkelstein Y, Adams-Webber T, et al. Do antipyretics prevent the recurrence of febrile seizures in children? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2013;17(6):585-588. (Systematic review; 3 studies, 540 patients) DOI: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2013.04.008

61. * Offringa M, Newton R, Nevitt SJ, et al. Prophylactic drug management for febrile seizures in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;6(6):CD003031. (Cochrane review; 32 trials, 4431 patients) DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003031.pub4

Subscribe to get the full list of 76 references and see how the authors distilled all of the evidence into a concise, clinically relevant, practical resource.

Keywords: fever, seizure, pediatric fever, pediatric seizure, febrile seizure, simple febrile seizure, complex febrile seizure, status epilepticus, febrile status epilepticus, lumbar puncture, electroencephalograph, EEG, antipyretic, benzodiazepine, antiseizure medication, anticipatory guidance