Table of Contents

About This Issue

Public health programs have helped decrease the prevalence and sequelae of vaccine-preventable diseases. However, vaccine failures, waning immunity, vaccine rejection, misinformation, public fear, and disruption of vaccination programs have led to community outbreaks and clinical sequelae in those exposed and affected. This issue provides a review of the clinical features, differential diagnoses, potential complications, and treatment options for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella. This information will enable emergency clinicians to readily identify the characteristic presentations of these infections, optimize supportive care, and give appropriate precautionary advice to patients and their families regarding complications. In this issue, you will learn:

The transmission route, incubation period, and isolation period of measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella

How effective live-attenuated vaccines are against these diseases

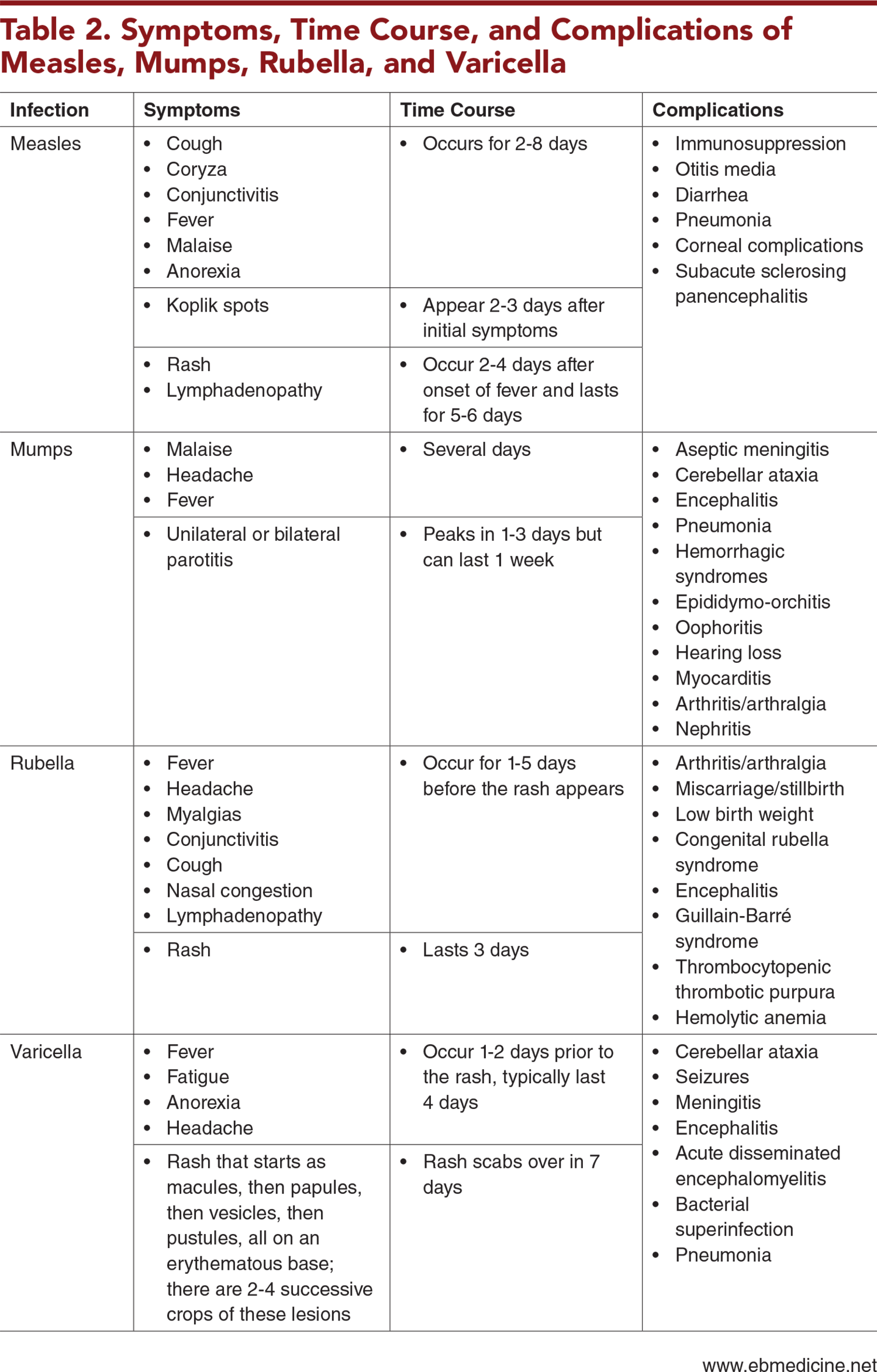

The symptoms, time course, and complications of measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella

The broad list of potential etiologies in the differential diagnosis for diseases presenting with fever and rash

Key questions to ask when obtaining the history

Guidance for performing the physical examination and findings that can help make the diagnosis

When diagnostic testing is indicated

Recommendations for general treatment as well as disease-specific treatment and postexposure prophylaxis

Adverse events that are associated with vaccines

The recommended vaccine schedule for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella

Which patients are at high risk for severe disease

Which patients should be hospitalized with isolation precautions, and which can be discharged home with proper precautions

- About This Issue

- Abstract

- Case Presentations

- Introduction

- Critical Appraisal of the Literature

- Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Measles

- Mumps

- Rubella

- Varicella

- Epidemiology

- Measles

- Mumps

- Rubella

- Varicella

- Presenting Clinical Features

- Measles

- Mumps

- Rubella

- Varicella

- Differential Diagnosis

- Prehospital Care

- Emergency Department Evaluation

- History

- Physical Examination

- General Examination

- Presentations Associated With These Diseases

- Diagnostic Studies

- Reporting Diagnosed Cases

- Isolation Precautions

- Treatment

- General Treatment

- Disease-Specific Treatment and Postexposure Prophylaxis

- Measles

- Mumps

- Rubella

- Varicella

- Adverse Events Associated With Vaccination

- Special Circumstances

- Patients at High Risk for Severe Disease

- Management of Contact Exposure

- Controversies and Cutting Edge

- Disposition

- Summary

- 5 Things That Will Change Your Practice

- Risk Management Pitfalls in Emergency Department Management of Patients With Measles, Mumps, Rubella, or Varicella

- Time- and Cost-Effective Strategies

- Case Conclusions

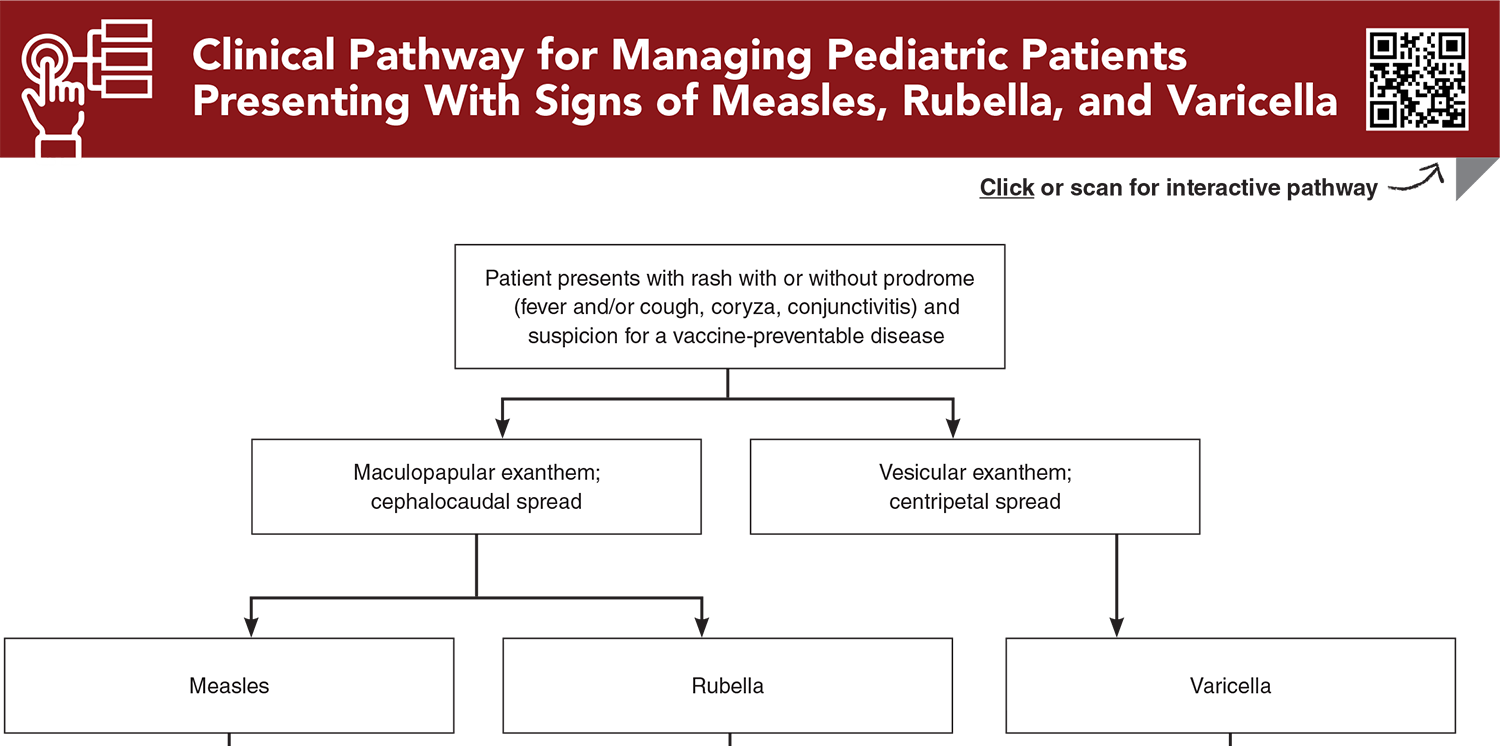

- Clinical Pathway for Managing Pediatric Patients Presenting With Signs of Measles, Rubella, and Varicella

- Tables, Figures, and Appendix

- References

Abstract

Public health programs have helped decrease the prevalence and sequelae of measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella; however, misinformation regarding vaccinations and recent disruptions to vaccination programs have caused outbreaks to occur. Emergency clinicians must be able to readily identify the characteristic presentations of measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella, with the goals of optimizing supportive care, limiting the spread of disease, and giving appropriate precautionary advice for complications to patients and their families. This issue provides a review of the clinical features, differential diagnoses, potential complications, and treatment options for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella.

Case Presentations

- The mother also tells you that the infant developed a red, raised rash on his face that spread to his abdomen and extremities over the course of a day. The mother reports that her son is eating less and has been breathing rapidly. The boy was born full-term in the United States and has no past medical history. He has had 1 vaccination visit at his primary care physician, at 2 months of age.

- The infant’s vital signs are: rectal temperature, 40°C; heart rate, 175 beats/min; blood pressure, 81/54 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 45 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 91% on room air. The physical examination is significant for rhinorrhea, lesions on the buccal mucosa, and bilateral conjunctival injection without purulent drainage. You note cervical lymphadenopathy and a blanching maculopapular exanthem on his face, trunk, extremities, palms, and soles. Upon auscultation, he has rales at both lung bases.

- You consider: What is the etiology for this patient’s fever and rash? What are the possible complications of his illness? Does this patient need diagnostic testing or specialty consultation? Should this patient be isolated in the ED, and should contacts be isolated or treated? What treatments are indicated? Should this patient be admitted?

- The mother tells you the rash began on the infant’s face as “water blisters.” The mother also states that it seems as though her daughter has not felt well for the last 2 days, has had decreased urine output, decreased activity, and has been irritable. According to the mother, the girl is up-to-date with recommended vaccinations for her age. There are no sick contacts in the family; however, the patient’s grandmother has a painful rash on her back.

- The infant’s vital signs are: rectal temperature, 38.5°C; heart rate, 170 beats/min; blood pressure, 100/64 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 40 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 98% on room air. The physical examination is significant for vesicles on an erythematous base on the girl’s face, trunk, extremities, and back, as well as many excoriated and scabbed lesions. There are erythematous papules on the anterior buccal mucosa and the posterior pharynx. The infant’s mucous membranes are dry, her lungs are clear, and her skin is warm. The infant is crying and her mother is having difficulty consoling her.

- Similar to your previous patient, you wonder: What is the etiology for this patient’s fever and rash? What are the possible complications of her illness? Does this patient need diagnostic testing or specialty consultation? Should this patient be isolated in the ED, and should contacts be isolated or treated? What treatments are indicated? Should this patient be admitted?

How would you manage these patients? Subscribe for evidence-based best practices and to discover the outcomes.

Clinical Pathway for Managing Pediatric Patients Presenting With Signs of Measles, Rubella, and Varicella

Subscribe to access the complete Clinical Pathway to guide your clinical decision making.

Tables, Figures, and Appendix

Subscribe for full access to all Tables, Figures, and Appendix.

Buy this issue and

CME test to get 4 CME credits.

Key References

Following are the most informative references cited in this paper, as determined by the authors.

1. * Anderer S. Global measles cases rose 20% in 1 year as vaccine coverage fell short. JAMA. 2025;333(4):279. (Review) DOI: 10.1001/jama.2024.25514

11. * United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chickenpox (varicella). Chickenpox vaccination. 2025. Accessed October 1, 2025. (National recommendation)

14. * United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles cases and outbreaks. 2025. Accessed October 1, 2025. (National recommendations)

17. * United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rubella (German measles, three-day measles): impact of U.S. MMR Vaccination Program. 2025. Accessed October 1, 2025. (National recommendations)

18. * Papania MJ, Wallace GS, Rota PA, et al. Elimination of endemic measles, rubella, and congenital rubella syndrome from the Western hemisphere: the US experience. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(2):148-155. (Expert review) DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4342

19. * Marin M, Meissner HC, Seward JF. Varicella prevention in the United States: a review of successes and challenges. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):e744-e751. (Review) DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-0567

32. * Ziebold C, von Kries Rd, Lang R, et al. Severe complications of varicella in previously healthy children in Germany: a 1-year survey. Pediatrics. 2001;108(5):e79. (Surveillance study; 119 children) DOI: 10.1542/peds.108.5.e79

39. * American Academy of Pediatrics. Measles. In: Kimberlin D, Banerjee R, Barnett E, et al, eds. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. 2024:570-585. (Expert recommendations) DOI: 10.1542/9781610027373-S3_012_002

43. * American Academy of Pediatrics. Mumps. In: Committee on Infectious Diseases, Kimberlin D, Banerjee R, et al, eds. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. 2024:611-616. (Expert recommendation) DOI: 10.1542/9781610027373-S3_012_009

44. * American Academy of Pediatrics. Rubella. In: Committee on Infectious Diseases, Kimberlin D, Banerjee R, et al, eds. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed.2024:735-741. (Expert recommendations) DOI: 10.1542/9781610027373-S3_017_009

46. * American Academy of Pediatrics. Varicella-zoster virus infections. In: Kimberlin D, Banerjee R, Barnett E, et al, eds. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed.2024:938-951. (Expert recommendations) DOI: 10.1542/9781610027373-S3_021_001

53. * Black S, Shinefield H, Ray P, et al. Postmarketing evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of varicella vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18(12):1041-1046. (Retrospective case control; 89,753 patients) DOI: 10.1097/00006454-199912000-00003

64. * Demicheli V, Rivetti A, Debalini MG, et al. Vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(2):CD004407. (Systematic review; 58 studies, 14,700,00 patients)

Subscribe to get the full list of 66 references and see how the authors distilled all of the evidence into a concise, clinically relevant, practical resource.

Keywords: measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, vaccine-preventable disease, vaccine-preventable illness, disease outbreak, rubeola, 3-day measles, German measles, congenital rubella syndrome, varicella-zoster, herpes zoster, shingles, viral disease, pediatric infections, vaccine, vaccination, vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal, MMR vaccine, MMRV vaccine, reporting, isolation precautions, postexposure prophylaxis, antiviral therapy, vaccine adverse events, vaccination schedule, contact exposure