Patients with maxillofacial trauma require careful evaluation due to the anatomical proximity of the maxillofacial region to the head and neck. Facial trauma can lead to life-threatening airway compromise or hemorrhage, or permanent facial deformity. Although the Advanced Trauma Life Support guidelines provide a framework for the management of trauma patients, they do not provide a detailed reference for many subtle or complex facial injuries. In addition to an overview of maxillofacial trauma pathophysiology, associated injuries, and physical examination, this review will also discuss relevant imaging, treatment, and disposition plans.

How would you manage these patients? Subscribe for evidence-based best practices and to discover the outcomes.

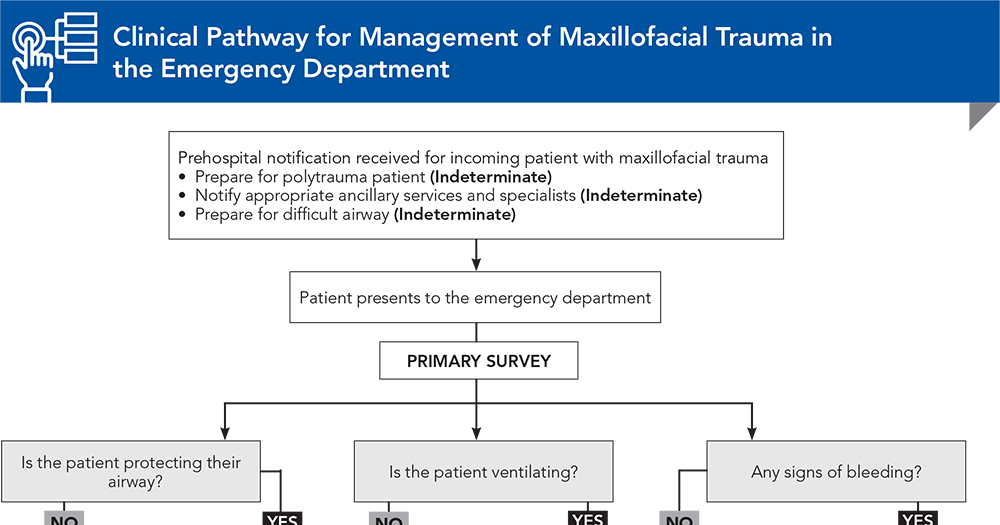

Subscribe to access the complete Clinical Pathway to guide your clinical decision making.

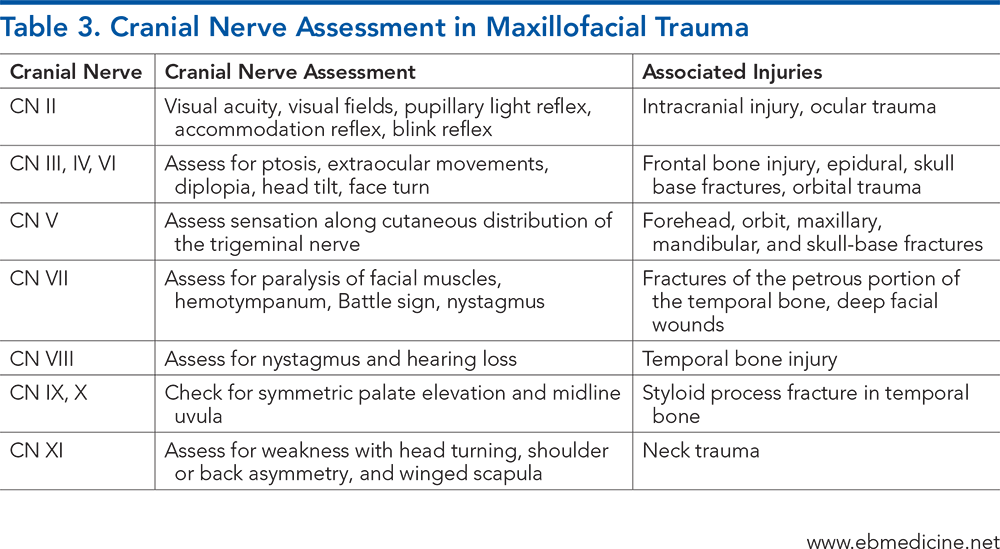

Subscribe for full access to all Tables and Figures.

Buy this issue and

Following are the most informative references cited in this paper, as determined by the authors.

2. * Perry M. Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) and facial trauma: can one size fit all? Part 1: dilemmas in the management of the multiply injured patient with coexisting facial injuries. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37(3):209-214. (Review article) DOI: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.11.003

15. * Kucik CJ, Clenney T, Phelan J. Management of acute nasal fractures. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70(7):1315-1320. (Review article) PMID: 15508543

17. * Tuckett JW, Lynham A, Lee GA, et al. Maxillofacial trauma in the emergency department: a review. Surgeon. 2014;12(2):106-114. (Review article) DOI: 10.1016/j.surge.2013.07.001

18. * Ceallaigh PÓ, Ekanaykaee K, Beirne CJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of common maxillofacial injuries in the emergency department. Part 5: dentoalveolar injuries. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(6):429-430. (Review article) DOI: 10.1136/emj.2006.035949

30. * Perry M, Dancey A, Mireskandari K, et al. Emergency care in facial trauma--a maxillofacial and ophthalmic perspective. Injury. 2005;36(8):875-896. (Review article) DOI: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.09.018

31. * Perry M, Morris C. Advanced trauma life support (ATLS) and facial trauma: can one size fit all? Part 2: ATLS, maxillofacial injuries and airway management dilemmas. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37(4):309-320. (Review article) DOI: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.11.002

42. * Ceallaigh PÓ, Ekanaykaee K, Beirne CJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of common maxillofacial injuries in the emergency department. Part 1: advanced trauma life support. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(10):796-797. (Review article) DOI: 10.1136/emj.2006.035931

55. * Dolan KD, Jacoby CG, Smoker WRK. The radiology of facial fractures. Radiographics. 1984;4(4):577-663. (Review article) DOI: 10.1148/radiographics.4.4.577

68. * Kellman RM, Tatum SA. Pediatric craniomaxillofacial trauma. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2014;22(4):559-572. (Review article) DOI: 10.1016/j.fsc.2014.07.009

Subscribe to get the full list of 79 references and see how the authors distilled all of the evidence into a concise, clinically relevant, practical resource.

Keywords: maxillofacial trauma, craniofacial trauma, facial trauma, mandibular fracture, maxillary fracture, zygoma fracture, cervical spine injury, nasal fracture, orbital fracture, Le Fort fracture, cranial nerve, blowout fracture, mandibular dislocation, orbital compartment syndrome

Reena Sheth, MD; Rebecca K. Smith, ScB; Janelle S. Lambert, MD, MS-HPEd

Michael P. Jones, MD, FACEP, FAAEM; Drew Clare, MD

October 15, 2024

October 15, 2027 CME Information

4 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™, 4 AOA Category 2-B Credits. Specialty CME Credits: Included as part of the 4 credits, this CME activity is eligible for 4 Trauma credits, subject to your state and institutional approval.