Table of Contents

About This Issue

Many low-voltage electrical injuries can be managed and discharged from urgent care. Proper management hinges on identifying the type of exposure, with low-risk cases manageable in urgent care, while high-risk injuries necessitate transfer to a higher level of care. In this issue, you will learn:

The types of exposures associated with low-voltage and high-voltage electrical injuries, and the physiological effects of these injuries

How to differentiate between low-risk and high-risk injuries based on factors such as voltage, duration of contact, affected body areas, and associated symptoms

Which diagnostic studies are indicated for low-voltage electrical injuries

How to identify which patients require transfer to an ED or specialized burn center for further evaluation and management

Management strategies for patients with more severe injuries who are awaiting EMS transfer

The follow-up care recommendations required to monitor for delayed complications and ensure optimal recovery

KidBits: Special considerations for pediatric patients with electrical injuries

CODING & CHARTING: Coding for electrical injuries will be guided by the extent of the injury. Learn more in our monthly coding column.

- About This Issue

- Abstract

- Case Presentations

- Introduction

- Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Lightning Strike

- Differential Diagnosis

- Cardiovascular Injury

- Neurologic Injury

- Cutaneous Injury

- Other Injuries

- Urgent Care Evaluation

- Initial Assessment

- History

- Physical Examination

- Diagnostic Studies

- Low-Risk Criteria

- High-Risk Criteria

- Treatment

- Wound Management

- Oral Commissure Burns

- Cardiac Arrhythmia or Heart Block

- Special Populations

- Pregnant Patients

- Electrical Control Device Injuries

- KidBits: Electrical Injury in the Pediatric Population

- Urgent Care Triage and Diagnosis

- Treatment

- Discharge Planning

- KidBits References

- Controversies

- Parenteral Antibiotics

- Disposition

- Transfer

- Discharge

- Follow-Up Care

- Case Conclusions

- Summary

- Time- and Cost-Effective Strategies

- 3 Things That Will Change Your Practice

- Risk Management Pitfalls for Management of Electrical Injuries in Urgent Care

- Critical Appraisal of the Literature

- Coding & Charting: What You Need to Know

- Number and Complexity of Problems Addressed

- Amount and/or Complexity of Data to be Reviewed and Analyzed

- Risk of Complications and/or Morbidity or Mortality of Patient Management

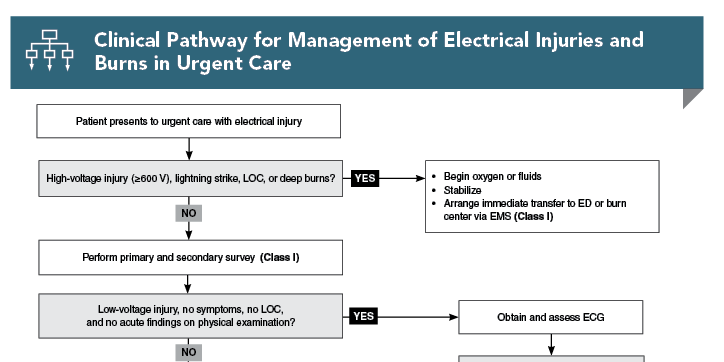

- Clinical Pathway for Management of Electrical Injuries and Burns in Urgent Care

- References

Abstract

Electrical injuries cause approximately 1000 deaths per year in the United States, most often due to either high-voltage electrical injury or lightning strike. However, an additional approximately 30,000 nonfatal shocks occur annually. The type of exposure will guide the management strategy for patients with electrical injury. While most patients with low-risk injuries can be safely managed in and discharged from urgent care, clinicians must be able to recognize high-risk injuries that require transfer to a higher level of care. This review provides evidence-based recommendations for the evaluation and management of electrical injuries in the urgent care setting, including indications for referral to an emergency department or comprehensive burn center.

Case Presentations

- The cord was connected to a lamp that was plugged into a wall outlet in the family’s home.

- The patient is calm in his mother’s lap. The event occurred 1 hour before arrival, when the parents noticed a ”rash” on the right side of the boy’s lips. They report no other symptoms.

- The patient has stable vital signs. On physical examination, you notice a white and gray eschar to the right oral commissure that is not actively bleeding, with surrounding erythema to the facial skin. There are no intraoral, intranasal, or tongue lesions.

- The parents ask, ”What do we do for the burn, and is his mouth okay?”

- The event occurred 20 minutes before her arrival at the urgent care clinic. The patient notes that she feels anxious.

- She denies loss of consciousness, lightheadedness, chest pain, heart palpitations, trouble breathing, nausea, abdominal pain, and pain or paresthesia to the affected hand. The patient is left-hand dominant.

- Her vital signs are stable. On physical examination, you note no abnormalities, including entrance or exit wounds or burns to the skin. She is neurovascularly intact to the left hand.

- The patient asks, “Am I okay? I feel funny...”

- The event occurred 40 minutes before arrival at the clinic. The patient complains of left wrist pain.

- He denies loss of consciousness, lightheadedness, chest pain, heart palpitations, trouble breathing, nausea, or abdominal pain.

- The patient says he does not believe he has any other injuries or retained barbs in his body. He notes that he is right-hand dominant.

- His vital signs are stable. On physical examination, you note tenderness to the left lateral wrist, with decreased range of motion secondary to pain. He is neurovascularly intact to the right upper extremity.

- After the exam, the patient asks, “Can I just leave now?”

How would you manage these patients? Subscribe for evidence-based best practices and to discover the outcomes.

Clinical Pathway for Management of Electrical Injuries and Burns in Urgent Care

Subscribe to access the complete Clinical Pathway to guide your clinical decision making.

Buy this issue and

CME test to get 4 CME credits.

Key References

Following are the most informative references cited in this paper, as determined by the authors.

2. * Rabban JT, Blair JA, Rosen CL, et al. Mechanisms of pediatric electrical injury. New implications for product safety and injury prevention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(7):696-700. (Case series; 144 pediatric and adolescent patients) DOI: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170440058010

3. * Gurbuz K, Demir M. Patterns and outcomes of high-voltage vs low-voltage pediatric electrical injuries: an 8-year retrospective analysis of a tertiary-level burn center. J Burn Care Res. 2022;43(3):704-709. (Retrospective analysis; 2243 patients) DOI: 10.1093/jbcr/irab178

9. * O’Keefe Gatewood M, Zane RD. Lightning injuries. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2004;22(2):369-403. (Review) DOI: 10.1016/j.emc.2004.02.002

10. * Spies C, Trohman RG. Narrative review: electrocution and life-threatening electrical injuries. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(7):531-537. (Narrative review) DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-7-200610030-00011

19. * Davis C, Engeln A, Johnson EL, et al. Wilderness Medical Society practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of lightning injuries: 2014 update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2014;25(4 Suppl):S86-S95. (Practice guidelines) DOI: 10.1016/j.wem.2014.08.011

27. * O’Keefe KP. Electrical injuries and lightning strikes: evaluation and management. In: Danzel DF, Moreira ME, eds. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer; 2024. (Online textbook chapter)

28. * American Burn Association. Guidelines for Burn Patient Referral. Accessed March 10, 2024. (Practice guidelines)

32. * Haileyesus T, Annest JL, Mercy JA. Non-fatal conductive energy device-related injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2005-2008. Inj Prev. 2011;17(2):127-130. (Retrospective study; 75,000 patients per year) DOI: 10.1136/ip.2010.028704

34. * Kroll MW, Lakkireddy DR, Stone JR, et al. TASER electronic control devices and cardiac arrests: coincidental or causal? Circulation. 2014;129(1):93-100. (Response article) DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004401

Subscribe to get the full list of 39 references and see how the authors distilled all of the evidence into a concise, clinically relevant, practical resource.

Keywords: electrical, low voltage, high voltage, current, shock, burn, oral commissure, lightning strike, arrhythmia, compartment syndrome, TASER, myoglobinuria, Rule of 9s, Lund Browder, Parkland formula, modified Brooke formula