Suicide is a leading cause of death among youth, and the emergency department (ED) serves as the primary point of healthcare contact for many with suicidal ideation. As suicide-related presentations to the ED continue to rise, the implementation of time- and cost-effective care pathways becomes ever more critical. Evidence-based tools for the identification and stratification of suicide risk can aid in clinical decision-making and care linkage. This issue reviews best practices for suicide risk assessment of youth to guide evaluation, management, and disposition planning within the ED setting.

How would you manage these patients? Subscribe for evidence-based best practices and to discover the outcomes.

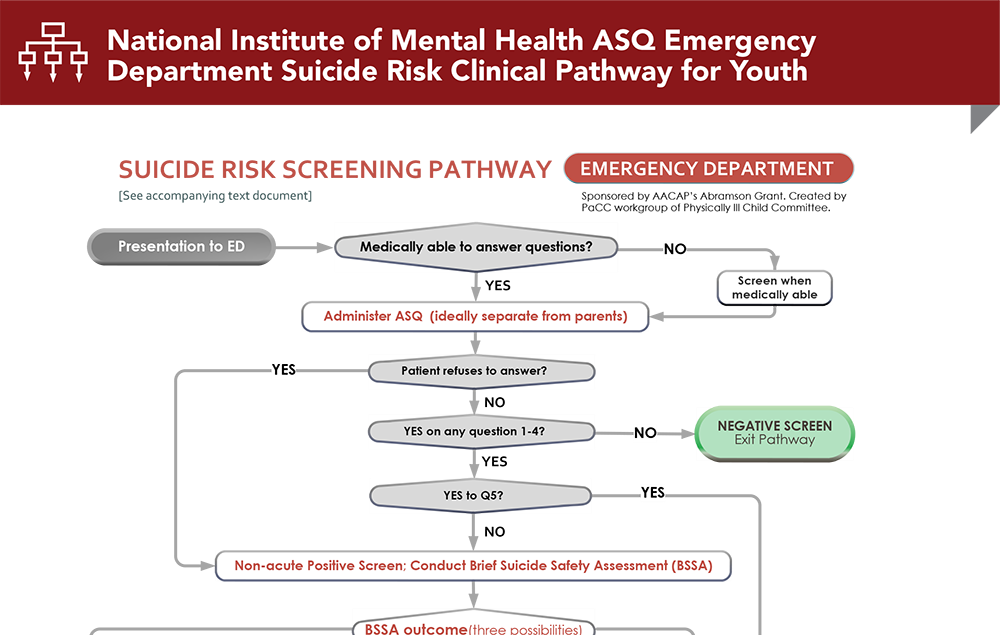

Subscribe to access the complete flowchart to guide your clinical decision making.

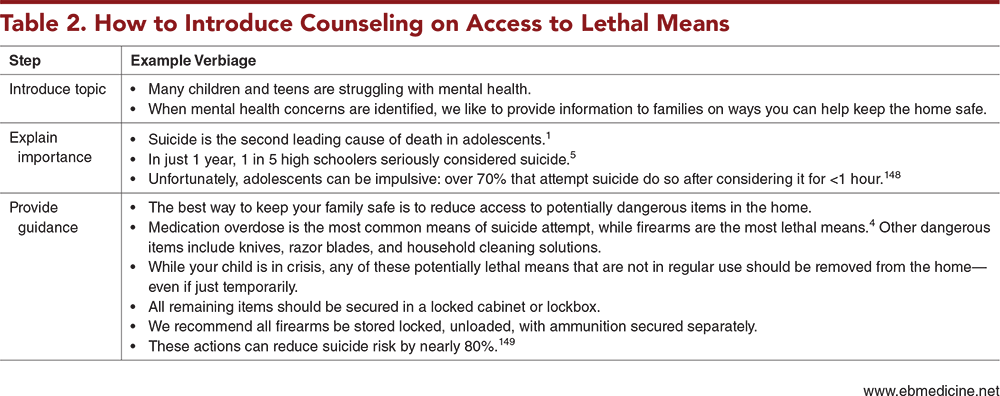

Subscribe for full access to all Tables and Figures.

Following are the most informative references cited in this paper, as determined by the authors.

1. * American Academy of Pediatrics and American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Suicide: blueprint for youth suicide prevention. Accessed February 1, 2024. (Report)

7. * King CA, Grupp-Phelan J, Brent D, et al. Predicting 3-month risk for adolescent suicide attempts among pediatric emergency department patients. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(10):1055-1064. (Prospective observational study; 2897 participants) DOI: 10.1111/jcpp.13087

13. * Doupnik SK, Rudd B, Schmutte T, et al. Association of suicide prevention interventions with subsequent suicide attempts, linkage to follow-up care, and depression symptoms for acute care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(10):1021-1030. (Systematic review and meta-analysis; 14 studies, 4270 patients) DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1586

34. * Hughes JL, Horowitz LM, Ackerman JP, et al. Suicide in young people: screening, risk assessment, and intervention. BMJ. 2023;381:e070630. (Review) DOI: 10.1136/bmj-2022-070630

64. * Horowitz LM, Bridge JA, Teach SJ, et al. Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ): a brief instrument for the pediatric emergency department. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1170-1176. (Instrument validation study) DOI: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1276

138. *King CA, Brent D, Grupp-Phelan J, et al. Prospective development and validation of the computerized adaptive screen for suicidal youth. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(5):540-549. (Prospective multicenter study; 2075 adolescents) DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4576

150. *Stanley B, Brown GK, Brenner LA, et al. Comparison of the safety planning intervention with follow-up vs usual care of suicidal patients treated in the emergency department. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(9):894-900. (Comparative study; 1640 patients) DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1776

160. *United States Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Critical crossroads pediatric mental health care in the emergency department: a care pathway resource toolkit. 2019. Accessed, February 1, 2024. (Toolkit)

Subscribe to get the full list of 171 references and see how the authors distilled all of the evidence into a concise, clinically relevant, practical resource.

Keywords: suicide, suicidal ideation, suicidality, suicidal thoughts, suicidal behaviors, suicide attempt, self-harm, self-inflicted injuries, suicide screening, Ask Suicide-Screening Questions, ASQ, Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, C-SSRS, suicide assessment, Brief Suicide Safety Assessment, BSSA, Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage Risk Stratification, SAFE-T, intentional ingestion, safety planning, no-suicide contract, suicide-prevention contracting, lethal means counseling, Stanley-Brown Safety Plan, computerized adaptive testing, CAP, computerized adaptive screen for suicidal youth, CASSY

Ashley A. Foster, MD; Bijan Ketabchi, MD, MPH; Jennifer A. Hoffmann, MD, MS

Kathleen Berg, MD, FAAEM, FACEP; Genevieve Santillanes, MD, FACEP

March 1, 2024

March 1, 2027 CME Information

4 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™, 4 ACEP Category I Credits, 4 AAP Prescribed Credits, 4 AOA Category 2-B Credits. Specialty CME Credits: Included as part of the 4 credits, this CME activity is eligible for 4 Behavioral Health CME credits, subject to your state and institutional approval.