Table of Contents

About This Issue

Status epilepticus (SE) is the most extreme form of seizure disorder, and it is associated with up to 30% morbidity and mortality in adults. This issue presents a guideline-driven, algorithmic approach to management of SE, convulsive as well as nonconvulsive forms, and emphasizes the importance of determination of the underlying causes of the seizures. In this issue, you will learn:

The classifications of SE with and without prominent motor symptoms, which can help emergency clinicians differentiate SE from mimics, other seizure disorders, and other etiologies

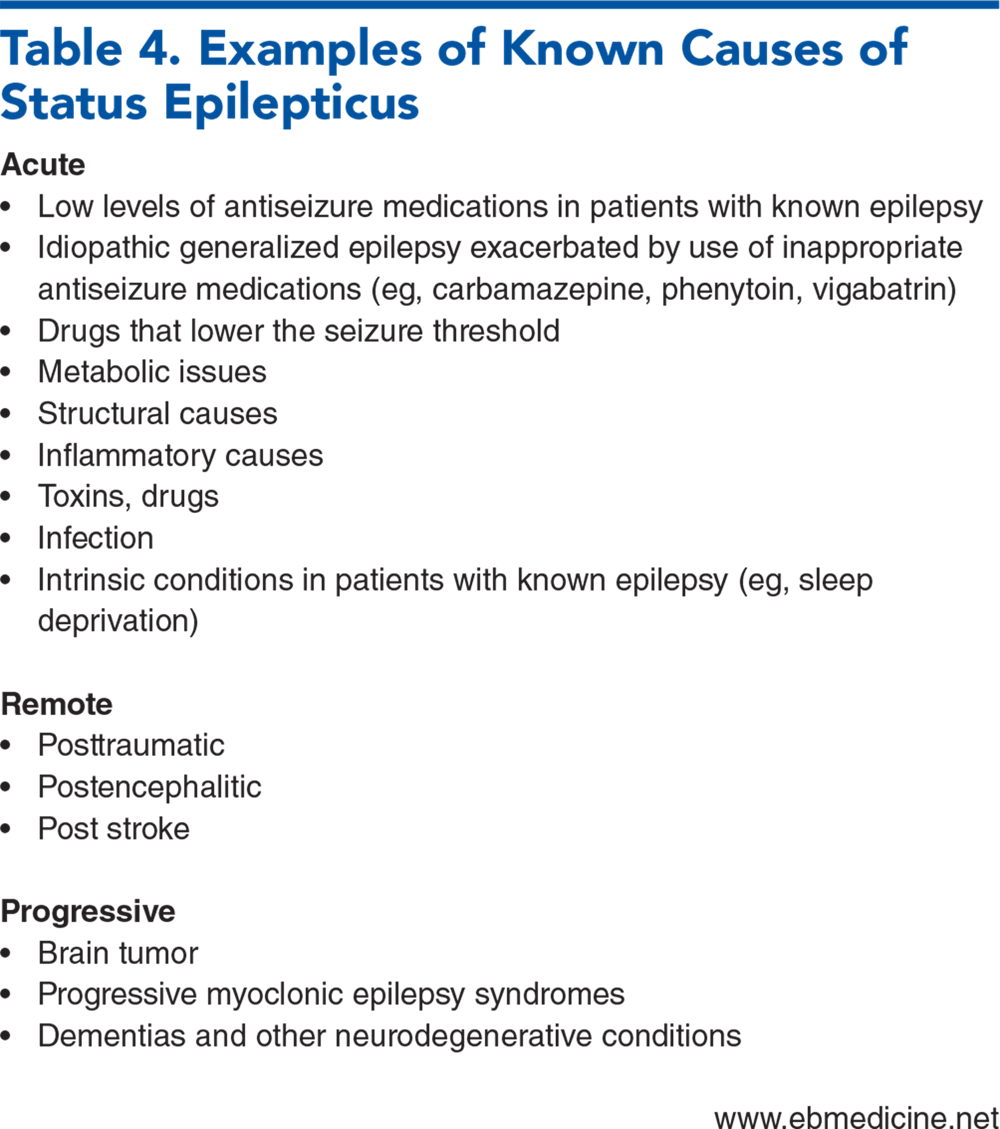

How to rule out causes of SE: acute, remote, and progressive

Laboratory testing that can assist in determining underlying causes for seizures

The guideline-recommended dosages of first-line benzodiazepines for seizures

Side-effect profiles to consider when a second-line seizure medication is necessary

How to manage refractory and super-refractory SE with third-line infusion anesthetic agents, and when EEG monitoring is necessary

Special management requirements for pregnant patients presenting with SE

- About This Issue

- Abstract

- Case Presentations

- Introduction

- Critical Appraisal of the Literature

- Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Definitions

- Pathophysiology

- Acute and Nonacute Etiologies

- Acute Etiologies

- Nonacute Etiologies

- Refractory Status Epilepticus

- Differential Diagnosis

- Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures

- Prehospital Care

- Emergency Department Evaluation

- History

- Physical Examination

- Diagnostic Studies

- Laboratory Testing

- Imaging Studies

- Lumbar Puncture

- Electroencephalogram Monitoring

- Monitoring for Subclinical Seizures

- Treatment

- Benzodiazepine Treatment

- Medications for Benzodiazepine-Refractory Convulsive Status Epilepticus

- Lacosamide

- Levetiracetam, Valproate, and Phenytoin

- Second-Line Antiseizure Medications Summary

- Management of Refractory and Super-Refractory Status Epilepticus

- Special Populations

- Substance-Induced Status Epilepticus

- Pregnant Patients

- Pediatric Patients

- Controversies and Cutting Edge

- Ketamine for Refractory Status Epilepticus

- Ganaxolone

- Thrombolysis for Patients With Todd Paralysis

- Emerging Technologies for Electroencephalogram Monitoring

- Disposition

- Summary

- Time- and Cost-Effective Strategies

- 5 Things That Will Change Your Practice

- Risk Management Pitfalls in Managing Status Epilepticus in the Emergency Department

- Case Conclusions

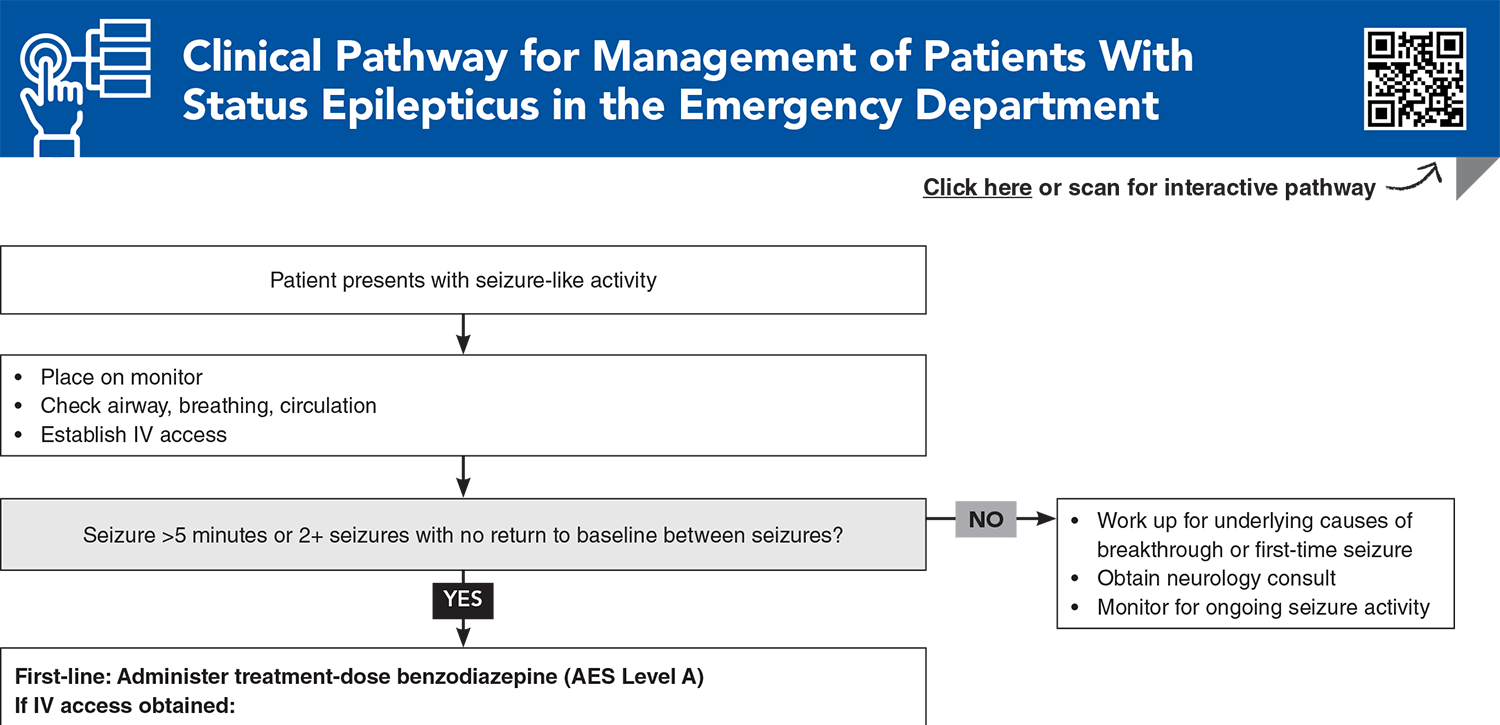

- Clinical Pathway for Management of Patients With Status Epilepticus in the Emergency Department

- Tables

- References

Abstract

Status epilepticus is a neurological emergency requiring prompt intervention by emergency clinicians, as delays can lead to significant morbidity and mortality. Etiologies include acute causes such as electrolyte imbalance, infection, drugs, and acute strokes, as well as chronic causes such as remote brain injury, progressive epilepsies, and brain tumors. This issue presents evidence for an algorithmic approach to status epilepticus, from managing underlying causes and administering initial benzodiazepines, to second-line antiseizure agents, and escalating to intravenous anesthetics for refractory cases. Disposition for patients in status epilepticus includes inpatient care tailored to the patient’s clinical needs, and appropriate follow-up.

Case Presentations

- EMS administered oxygen and 10 mg intramuscular midazolam, without resolution of symptoms. The patient was placed on a monitor, and IV access was obtained.

- Initial vital signs are: temperature, 37.3°C; heart rate, 120 beats/min; blood pressure, 157/90 mm Hg; and oxygen saturation, 98% on 4 L nasal cannula. A point-of-care glucose level is 81 mg/dL.

- After administration of 4 mg IV lorazepam, he stops seizing. You send initial blood work, including CBC, comprehensive metabolic profile, ethanol level, acetaminophen/salicylate level, and lactate, to the laboratory. His wife arrives and provides history that the patient is receiving radiation and chemotherapy for glioblastoma multiforme of the left temporal lobe.

- After 1 hour, the patient is still not responding to questioning or painful stimulus, and his oxygen requirement worsens. He has slight twitching movements of the right face and mouth every 2 minutes.

- You consider whether the patient could still be seizing and, if so, what the best next course of action should be...

- Her vital signs include: temperature, 37.6°C; heart rate, 110 beats/min; blood pressure, 140/80 mm Hg; and oxygen saturation, 99%.

- In speaking with her family, you note that she has a past psychiatric history that includes episodes of “poor impulse control” and “outbursts of violent behavior toward family members.”

- You consider whether she should be triaged to psychiatry or if something else might be going on…

How would you manage these patients? Subscribe for evidence-based best practices and to discover the outcomes.

Clinical Pathway for Management of Patients With Status Epilepticus in the Emergency Department

Subscribe to access the complete Clinical Pathway to guide your clinical decision making.

Tables

Subscribe for full access to all Tables.

Buy this issue and

CME test to get 4 CME credits.

Key References

Following are the most informative references cited in this paper, as determined by the authors.

1. * Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus—report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015;56(10):1515-1523. (Consensus statement) DOI: 10.1111/epi.13121

2. * Brophy GM, Bell R, Claassen J, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2012;17(1):3-23. (Guideline) DOI: 10.1007/s12028-012-9695-z

3. * Glauser T, Shinnar S, Gloss D, et al. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in children and adults: report of the Guideline Committee of the American Epilepsy Society. Epilepsy Curr. 2016;16(1):48-61. (Guideline) DOI: 10.5698/1535-7597-16.1.48

40. * Alldredge BK, Gelb AM, Isaacs SM, et al. A comparison of lorazepam, diazepam, and placebo for the treatment of out-of-hospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):631-637. (Randomized controlled trial; 205 patients) DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa002141

45. * Kapur J, Elm J, Chamberlain JM, et al. Randomized trial of three anticonvulsant medications for status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(22):2103-2113. (Randomized controlled trial; 384 patients) DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1905795

50. * Kanner AM, Bicchi MM. Antiseizure medications for adults with epilepsy: a review. JAMA. 2022;327(13):1269-1281. (Review) DOI: 10.1001/jama.2022.3880

54. * Shin J-W. Management strategies for refractory status epilepticus. Journal of Neurocritcal Care. 2023;16(2):59-68. (Review) DOI: 10.18700/jnc.230037

Subscribe to get the full list of 75 references and see how the authors distilled all of the evidence into a concise, clinically relevant, practical resource.

Keywords: seizure, epilepsy, nonconvulsive, convulsive, electroencephalogram, myoclonic, tonic, benzodiazepine, midazolam, lorazepam, refractory, psychogenic