Table of Contents

About This Issue

Diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus are potentially fatal—yet largely preventable—illnesses. Even in resource-rich environments, the overall morbidity and mortality are significant, and thus immunization remains the absolute first-line intervention. Despite a carefully considered vaccination schedule that is designed to maximize safety and effectiveness, there has been an increase in certain vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States. Emergency clinicians should not only advocate for vaccination but also be able to recognize and manage these illnesses when they do occur. This issue discusses the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and current recommended management of pediatric diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus in the emergency department. In this issue, you will learn:

The pathophysiology of diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus

The various vaccines available for prevention of diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus, as well as the recommended vaccination schedule

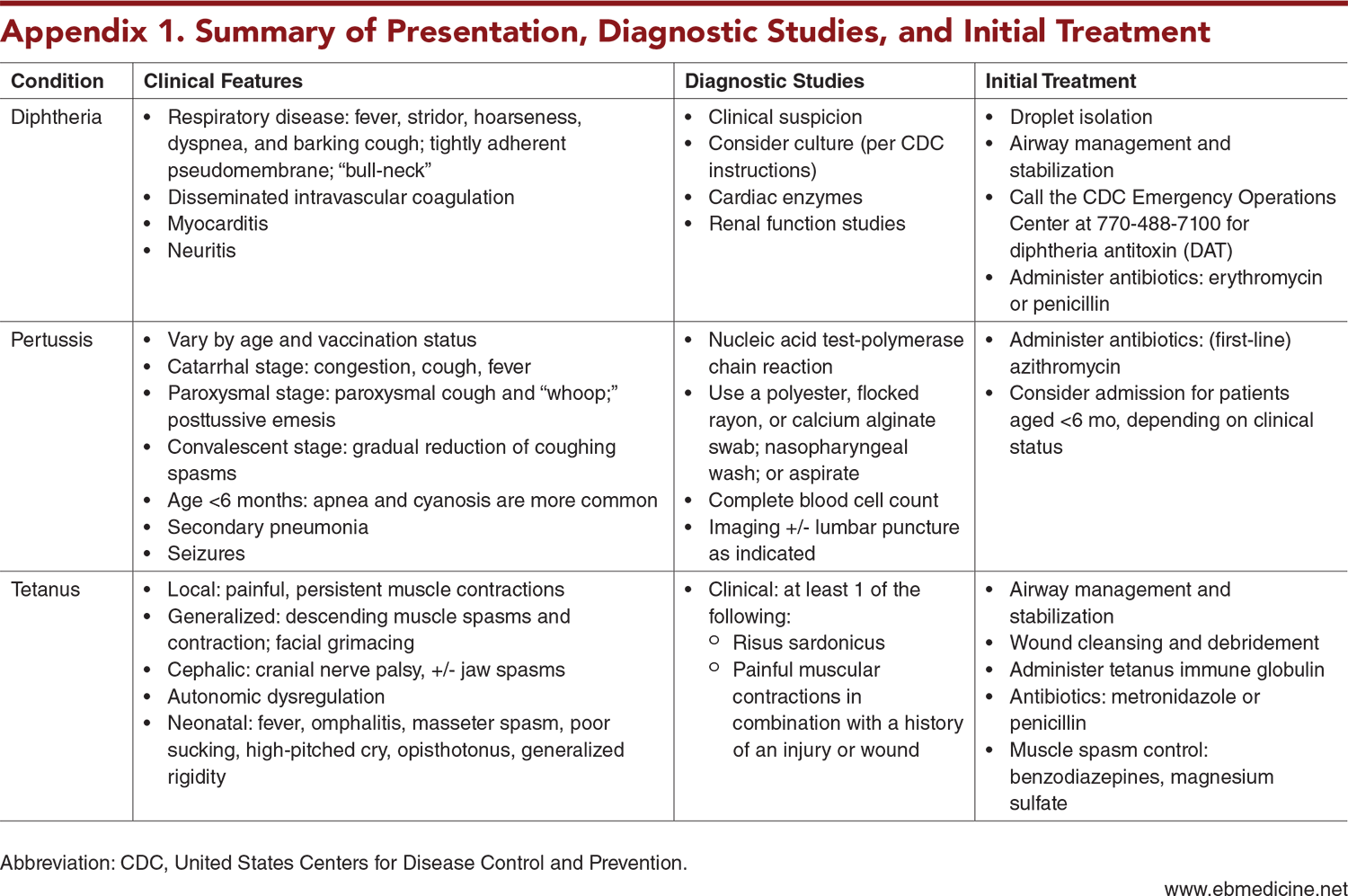

The clinical features of diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus

Which of these illnesses are diagnosed clinically, and when diagnostic studies are indicated

Evidence-based recommendations for treatment of diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus, as well as how to manage vaccine side effects and adverse events

Guidance for reporting and postexposure prophylaxis

Recommendations for managing close contacts of patients with diphtheria and pertussis

Which patients should be admitted and when patients can be discharged safely

- About This Issue

- Abstract

- Case Presentations

- Introduction

- Critical Appraisal of the Literature

- Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Etiology and Pathophysiology of Diphtheria

- Etiology and Pathophysiology of Pertussis

- Etiology and Pathophysiology of Tetanus

- Epidemiology and Prevalence

- Epidemiology and Prevalence of Diphtheria

- Epidemiology and Prevalence of Pertussis

- Epidemiology and Prevalence of Tetanus

- Vaccines for Diphtheria, Pertussis, and Tetanus

- Clinical Features

- Clinical Features of Diphtheria

- Clinical Features of Pertussis

- Clinical Features of Tetanus

- Differential Diagnosis

- Prehospital Care

- Emergency Department Evaluation

- History

- Physical Examination

- Diagnostic Studies

- Diagnostic Studies for Diphtheria

- Diagnostic Studies for Pertussis

- Diagnostic Studies for Tetanus

- Treatment

- Treatment for Diphtheria

- Diphtheria Antitoxin

- Antibiotic Therapy

- Immunization

- Treatment for Pertussis

- Antibiotic Therapy

- Treatment of Symptoms

- Immunization

- Treatment for Tetanus

- Reducing Circulating Toxin and Eradicating the Organism

- Controlling Muscle Spasms

- Benzodiazepines

- Magnesium Sulfate

- Other Medications

- Maintaining Autonomic Stability

- Wound Care

- Immunization

- Treatment of Vaccine Side Effects and Adverse Events

- Reporting Cases of Diphtheria, Pertussis, and Tetanus

- Special Circumstances

- Managing Close Contacts of Patients With Diphtheria

- Managing Close Contacts of Patients With Pertussis

- Controversies and Cutting Edge

- Vaccine Refusal

- Disposition

- 5 Things That Will Change Your Practice

- Additional Resources

- Risk Management Pitfalls for Emergency Department Patients with Diphtheria, Pertussis, or Tetanus

- Summary

- Time- and Cost-Effective Strategies

- Case Conclusions

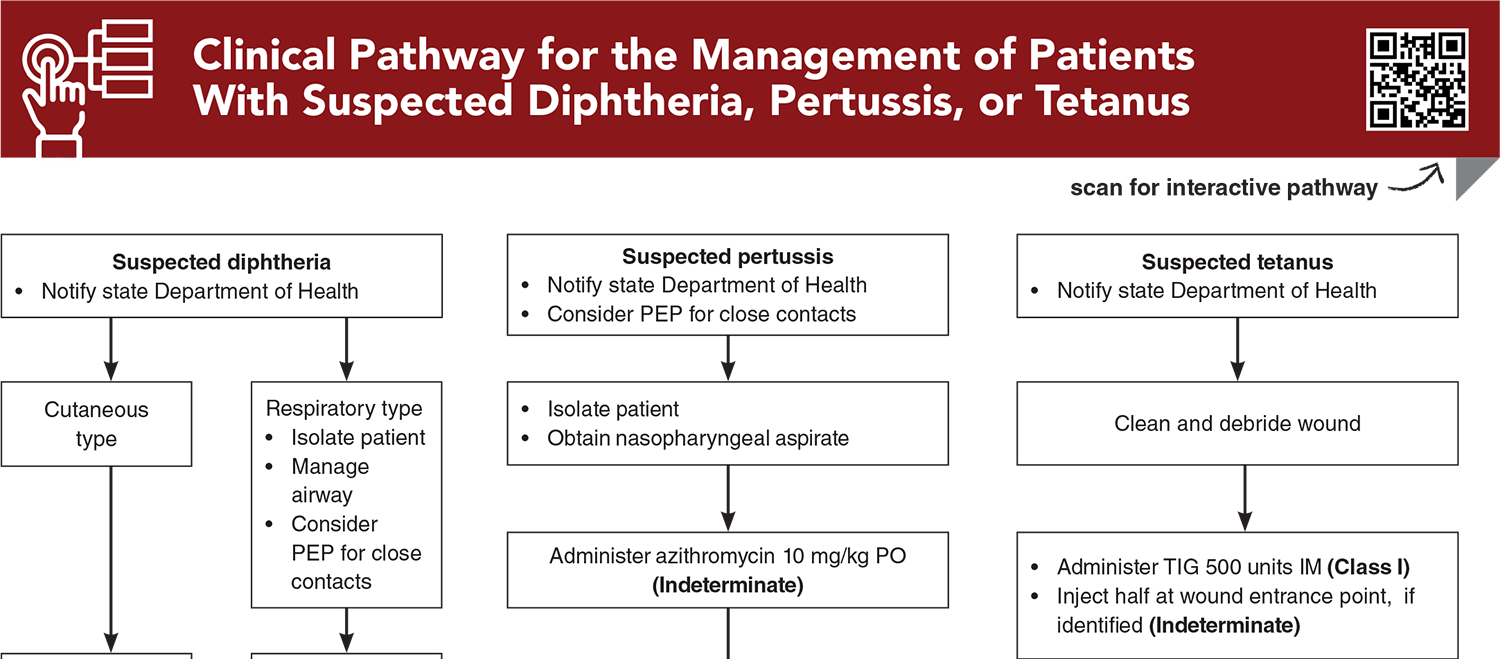

- Clinical Pathway for the Management of Patients With Suspected Diphtheria, Pertussis, or Tetanus

- Tables, Figures, and Appendix

- References

Abstract

Diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus are potentially deadly illnesses that are largely preventable through vaccination, though they remain in the population. This review discusses the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and current recommended management of these conditions in the emergency department. Disease-specific medications and treatment of secondary complications are reviewed in light of the best current evidence. Issues regarding vaccination and prevention are highlighted.

Case Presentations

- The parents tell you the girl has had recent congestion and a low-grade fever.

- In the ED, the child has a fever of 38ºC, a heart rate of 150 beats/min, a blood pressure of 75/45 mm Hg, and a respiratory rate of 35 breaths/min. On examination, there is inspiratory stridor, significant cervical lymphadenopathy, and a thick, grayish membrane coating the posterior pharynx. Chest examination reveals bilateral rales and tachycardia with frequent ectopic beats.

- Could this child have viral myocarditis associated with simple pharyngitis? You page the infectious disease specialist and ask the nurse to institute strict isolation precautions. What tests, if any, should you order to confirm your suspected diagnosis?

- In the resuscitation bay, the monitor shows a respiratory rate of 30 breaths/min, a heart rate of 140 beats/min, and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. The physical examination is unremarkable apart from occasional gagging. You note that the baby’s school-aged sibling begins coughing.

- What infectious etiology could explain these children’s very different presentations?

- The boy is holding a bandage to his foot. His parents report that he stepped on a nail while playing at a farm earlier that day.

- On examination, you note a small puncture wound that does not appear grossly soiled and is not actively bleeding. While taking the history, you learn the child is unimmunized and at risk for tetanus.

- It seems unlikely that you alone can change the parents’ minds about vaccines. Should you attempt to discuss the topic with the family? Should you call the primary care doctor and see if he or she can convince them? Could an antibiotic prevent tetanus from developing?

How would you manage these patients? Subscribe for evidence-based best practices and to discover the outcomes.

Clinical Pathway for Managing Patients Presenting with Acute Diarrhea in Urgent Care

Subscribe to access the complete Clinical Pathway to guide your clinical decision making.

Buy this issue and

CME test to get 4 CME credits.

Tables, Figures, and Appendix

Subscribe for full access to all Tables and Figures.

Key References

Following are the most informative references cited in this paper, as determined by the authors.

5. * United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diphtheria. In: Hamborsky J KA, Wolfe S, ed. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 14th ed. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation; 2021. (Textbook chapter)

13. * United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases; The Pink Book: Course Textbook. 14th ed. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation; 2021. (Textbook chapter)

17. * Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Diphtheria. In: Kimberlin DW, Banerjee R, Barnett ED, et al. eds. Red Book: 2024-2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024:325-329. (Textbook chapter) DOI: 10.1542/9781610027373

18. * Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Pertussis. In: Kimberlin DW, Banerjee R, Barnett ED, et al. eds. Red Book: 2024-2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024:659-667. (Textbook chapter) DOI: 10.1542/9781610027373

20. * United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tetanus. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases; The Pink Book: Course Textbook. 14th ed. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation; 2021. (Textbook chapter)

60. * Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Tetanus. In: Kimberlin DW, Banerjee R, Barnett ED, et al. eds. Red Book: 2024-2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024. (Textbook chapter) DOI: 10.1542/9781610027373

Subscribe to get the full list of 99 references and see how the authors distilled all of the evidence into a concise, clinically relevant, practical resource.

Keywords: diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, whooping cough, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Bordetella pertussis, Clostridium tetani, pseudomembrane, risus sardonicus, vaccine-preventable disease, vaccine-preventable illness, vaccine, vaccination, DTP, DTaP, Tdap, diphtheria antitoxin, DAT, tetanus immune globulin, TIG, postexposure prophylaxis, PEP, National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, vaccine refusal, vaccine hesitancy, vaccine hesitant