Table of Contents

About This Issue

Pediatric dehydration is a common cause for parents to bring their children into the emergency department for evaluation. Rehydration therapy should be tailored to the severity of illness, available resources, and the child’s clinical status. Clinical assessment of dehydration is challenging, as no single sign, symptom, or laboratory value reliably quantifies fluid deficit. This issue reviews the most recent updates in the evaluation of the pediatric patient with dehydration, offers guidance on the use of scoring systems to estimate the degree of dehydration, and provides recommendations for a systematic approach to manage these patients. In this issue, you will learn:

Reasons children are at a higher risk for volume loss and disruption of homeostasis after rapid total body water changes

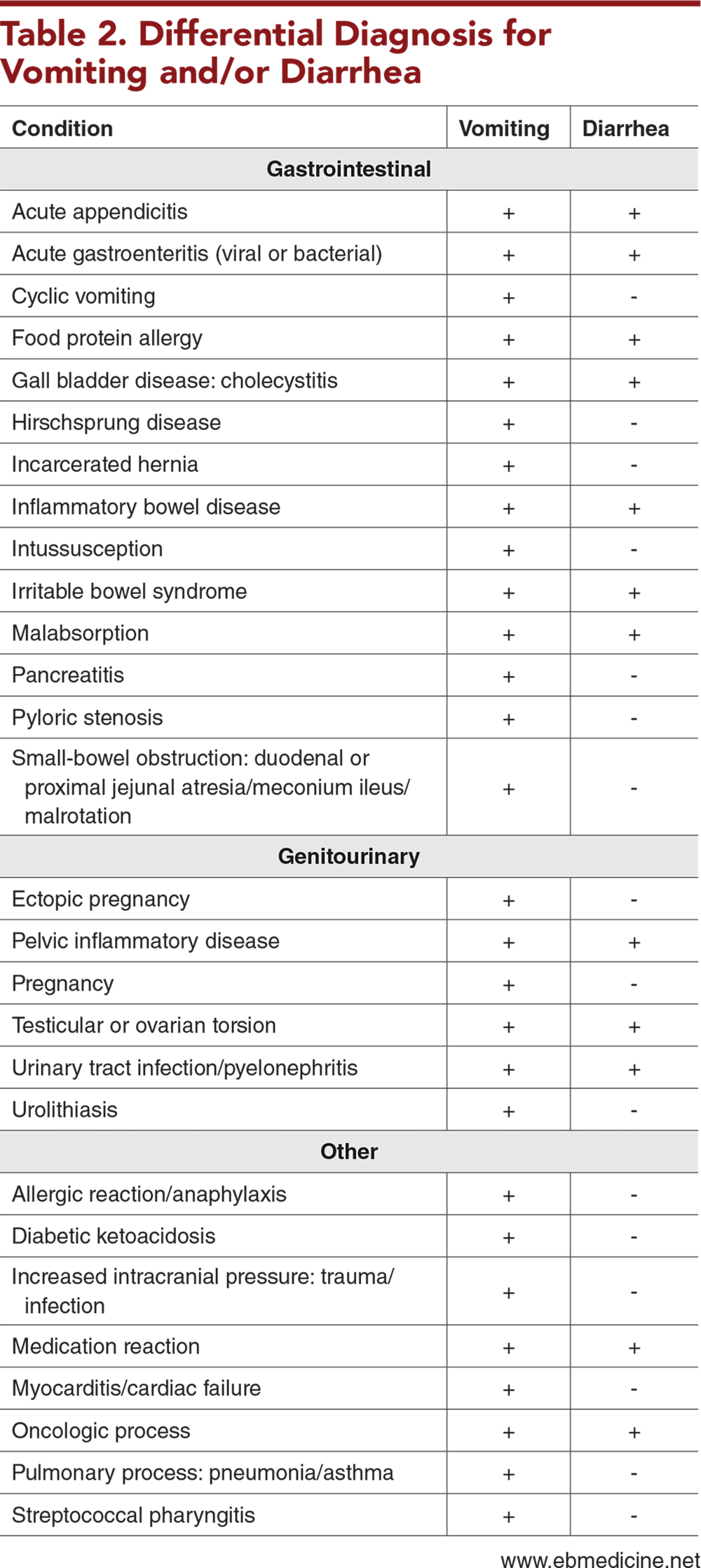

Conditions in the differential diagnosis of vomiting and/or diarrhea

Key questions to ask regarding the pediatric patient with potential dehydration

The most dependable clinical indicators of dehydration in children

Guidance for using scoring systems to determine the level of dehydration

Recommendations for improving the success of oral rehydration, and which methods of rehydration are good options when oral rehydration is not feasible

Which patients can be safely discharged home after appropriate rehydration and observation, and which patients need to be admitted

Advice to share with parents of children who are being discharged home

- About This Issue

- Abstract

- Case Presentations

- Introduction

- Critical Appraisal of the Literature

- Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Differential Diagnosis

- Prehospital Care

- Emergency Department Evaluation

- History

- Physical Examination

- Capillary Refill Time

- Skin Turgor

- Respiratory Pattern

- Determining the Level of Dehydration

- Charting Dehydration

- Newer Decision Tools

- Diagnostic Studies

- Urine Specific Gravity

- Serum Electrolytes

- Serum Bicarbonate

- Stool Testing

- Ova and Parasite Testing

- Point-of-Care Ultrasound

- Treatment

- Fluid Resuscitation

- Oral Rehydration Therapy

- Subcutaneous Hydration

- Intravenous Fluid Therapy

- Goal-Directed Therapy

- Diet

- Zinc and Probiotics

- Serial Assessments

- Advice for Parents

- Special Populations

- Controversies and Cutting Edge

- Subcutaneous Hydration With Recombinant Hyaluronidase

- Nasogastric Hydration

- Noninvasive Assessment of Bicarbonate

- Disposition

- Summary

- Key Points

- Findings on Physical Examination

- Management Considerations

- Time- and Cost-Effective Strategies

- 5 Things That Will Change Your Practice

- Risk Management Pitfalls for Emergency Department Management of Dehydration in Pediatric Patients

- Case Conclusions

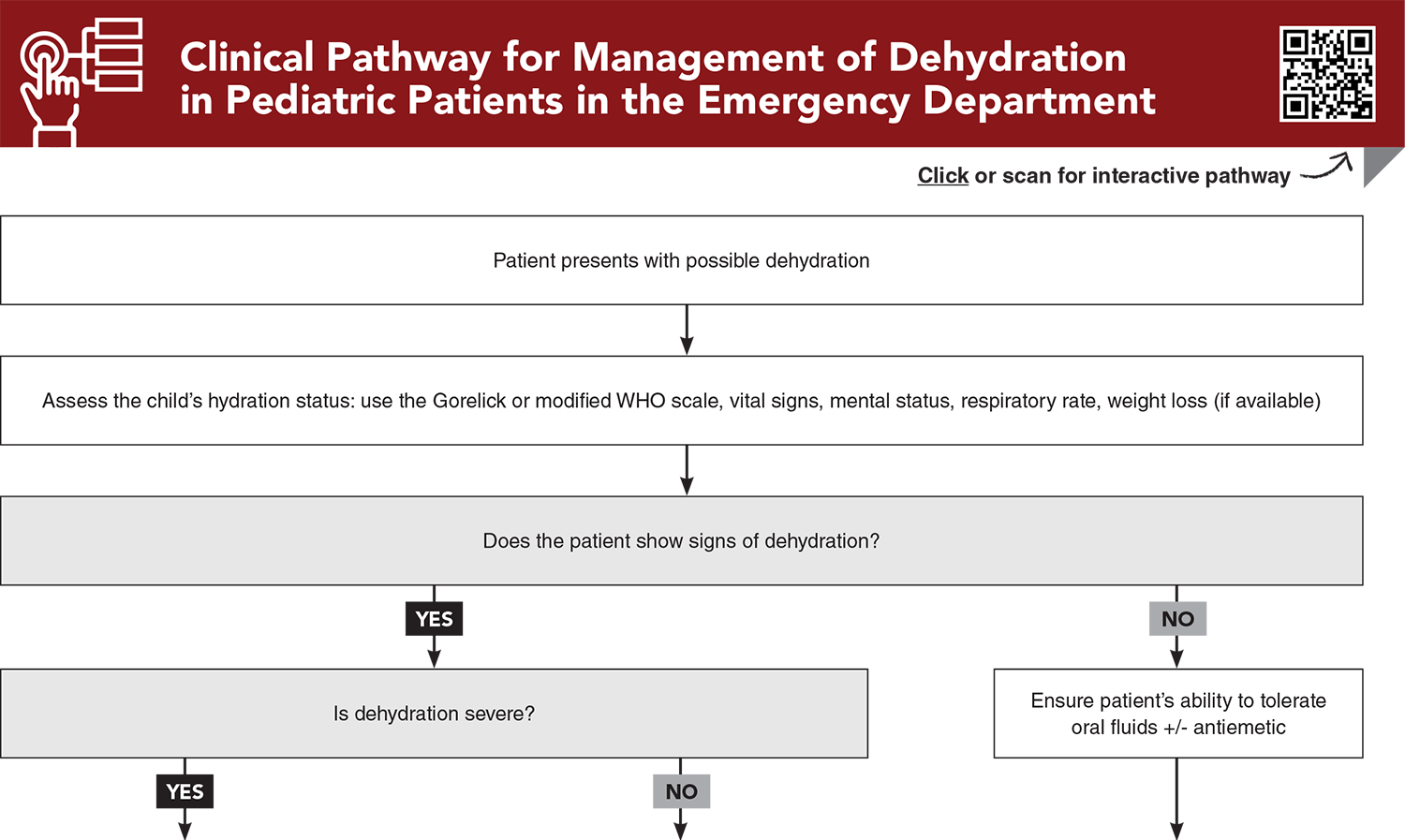

- Clinical Pathway for Management of Dehydration in Pediatric Patients in the Emergency Department

- Tables

- References

Abstract

Pediatric dehydration is a top concern that leads parents to bring their children into the emergency department for evaluation. Rehydration therapy should be tailored to the severity of illness, available resources, and the child’s clinical status. Although accurately determining the fluid deficit can be challenging, guidance is provided for use of scoring systems to estimate the degree of dehydration. Recommendations are given for first-line oral rehydration therapy, and for rehydration through intravenous, intraosseous, or subcutaneous methods when oral rehydration is not an option. A thoughtful, goal-directed approach that emphasizes timely rehydration, caregiver education, and careful follow-up can improve outcomes.

Case Presentations

- The mother tells you the girl has had profuse, watery, nonbloody diarrhea for the past 4 days.

- On examination, the girl is sleepy but arousable to stimulation before falling back to sleep. Her capillary refill time is 5 seconds, and she has cool distal extremities. Her vital signs are: temperature, 37.2°C; heart rate, 148 beats/min; blood pressure 72/56 mm Hg, and respiratory rate, 35 breaths/min.

- What is the primary goal of initial treatment for this patient?

- The mother tells you that the girl’s diarrhea has worsened over the past 2 days and is profuse, watery, and nonbloody. The girl had 2 episodes of vomiting.

- On examination, the girl is awake and upset. She is making tears during the examination and has warm distal extremities, with a capillary refill time of 3 seconds. Her vital signs are: temperature, 37.6°C; heart rate, 125 beats/min; blood pressure, 87/64 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 40 breaths/min.

- What clinical findings can reassure you about the degree of volume loss in this patient?

- The girl is awake and crying, but is consolable.

- She is making tears during the examination. She has warm distal extremities with a brisk capillary refill. Her vital signs are: temperature, 37.7°C; heart rate, 135 beats/min; blood pressure, 82/58 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 50 breaths/min.

- Does this infant require any treatment while in the emergency department?

How would you manage these patients? Subscribe for evidence-based best practices and to discover the outcomes.

Clinical Pathway for Managing Patients Presenting with Acute Diarrhea in Urgent Care

Subscribe to access the complete Clinical Pathway to guide your clinical decision making.

Tables

Subscribe for full access to all Tables.

Buy this issue and

CME test to get 4 CME credits.

Key References

Following are the most informative references cited in this paper, as determined by the authors.

2. * Gorelick MH, Shaw KN, Murphy KO. Validity and reliability of clinical signs in the diagnosis of dehydration in children. Pediatrics. 1997;99(5):E6. (Prospective cohort study; 186 children) DOI: 10.1542/peds.99.5.e6

3. * Steiner MJ, DeWalt DA, Byerley JS. Is this child dehydrated? JAMA. 2004;291(22):2746-2754. (Systematic review; 13 studies) DOI: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2746

9. * Levine AC, Gainey M, Qu K, et al. A comparison of the NIRUDAK models and WHO algorithm for dehydration assessment in older children and adults with acute diarrhoea: a prospective, observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11(11):e1725-e1733. (Prospective observational study; 1580 patients) DOI: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00403-5

14. * Wathen JE, MacKenzie T, Bothner JP. Usefulness of the serum electrolyte panel in the management of pediatric dehydration treated with intravenously administered fluids. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1227-1234. (Prospective study; 182 patients) DOI: 10.1542/peds.2004-0457

16. * Nagler J, Wright RO, Krauss B. End-tidal carbon dioxide as a measure of acidosis among children with gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):260-267. (Prospective study; 130 patients) DOI: 10.1542/peds.2005-2723

Subscribe to get the full list of 42 references and see how the authors distilled all of the evidence into a concise, clinically relevant, practical resource.

Keywords: dehydration, vomiting, diarrhea, fluid deficit, fluid loss, rehydration, fluid resuscitation, oral rehydration therapy, oral rehydration solution, intravenous therapy, subcutaneous hydration, nasogastric hydration, total body water, capillary refill, skin turgor, skin elasticity, respiratory pattern, classification of dehydration, clinical dehydration scale, Gorelick Scale, World Health Organization, WHO, Novel Innovative Research for Understanding Dehydration in Adults and Kids, NIRUDAK, Dehydration: Assessing Kids Accurately, DHAKA, urine specific gravity, serum electrolytes, serum bicarbonate, point-of-care ultrasound, goal-directed therapy, BRAT diet, zinc, probiotics