Table of Contents

- About This Issue

- Abstract

- Case Presentations

- Introduction

- Critical Appraisal of the Literature

- Definitions and Terminology

- Consensus Definitions and the United States Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Quality Measures

- Screening

- Epidemiology

- Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Differential Diagnosis

- Prehospital Care

- Emergency Department Evaluation

- History

- Physical Examination

- Diagnostic Studies

- Laboratory Testing

- Trending Lactate Levels

- Procalcitonin

- Imaging

- Treatment

- Initial Management

- Intravenous Fluids

- Positive Fluid Balance

- Patients With Obesity

- Patients at Risk for Fluid Overload

- Fluid Type

- Fluid Status Assessment

- Antibiotics

- Timing of Antibiotic Administration

- Antibiotic Coverage

- Vasopressors and Inotropes

- Central Versus Peripheral Access

- Norepinephrine

- Norepinephrine Versus Dopamine

- Vasopressin

- Epinephrine

- Dobutamine

- Phenylephrine

- Vasopressor Timing

- Corticosteroids

- Blood Transfusion

- Special Populations and Circumstances

- Controversies and Cutting Edge

- The Evidence Basis for CMS Bundle Metrics

- Sepsis Screening

- Methylene Blue

- Hydroxocobalamin

- Disposition

- End-of-Life Care

- Summary

- Time- and Cost-Effective Strategies

- Risk Management Pitfalls for Managing Emergency Department Patients With Sepsis

- 5 Things That Will Change Your Practice

- Disclaimer

- Case Conclusions

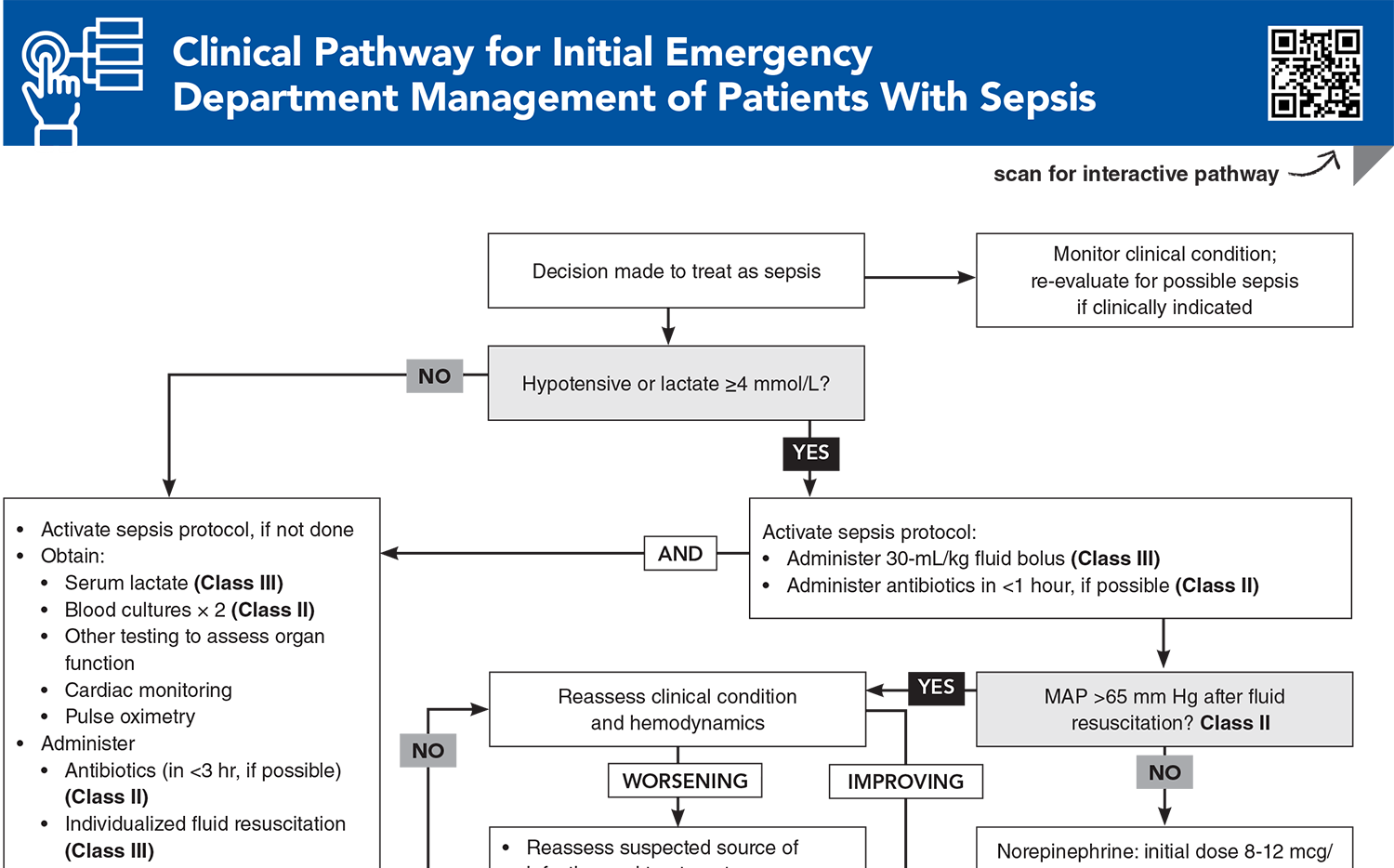

- Clinical Pathways

- Clinical Pathway for Sepsis Screening in the Emergency Department

- Clinical Pathway for Initial Emergency Department Management of Patients With Sepsis

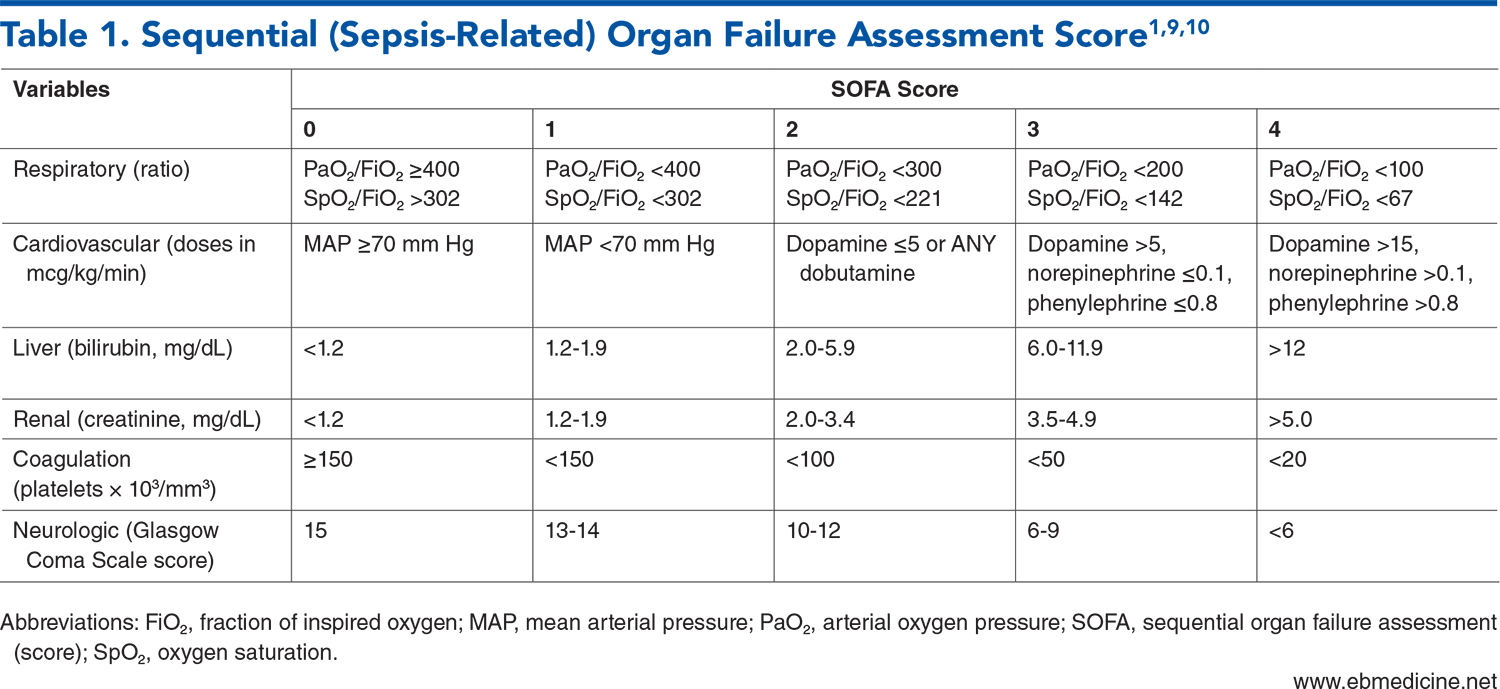

- Tables

- References

About This Issue

With the various sepsis/septic shock definitions, screening criteria, bundles, and CMS Quality Measures, it can be challenging to ensure that patients with suspected sepsis are being managed according to the best available evidence. This issue reviews the evolution of sepsis management and evaluates the latest evidence on management of this potentially life-threatening condition. In this issue, you will learn:

How the definitions of sepsis have changed over the last decades, based on screening criteria

How the current Sepsis-3 definitions vary from the CMS Sep-1 definitions

The advantages, disadvantages, and uses of the various screening tools for sepsis (SOFA, qSOFA, SIRS, NEWS, and MEWS)

How to organize an approach to sepsis diagnosis by organ system

Which laboratory tests and imaging strategies are essential in the ED, and which can be delayed or eliminated

What is required in the first 3 hours of management, and what is required in the first 6 hours

Fluids, antibiotics, vasopressors and inotropes, and corticosteroids: what should be given and when

Abstract

Sepsis is a common life-threatening condition that requires early recognition and prompt management. Diagnosis and treatment of sepsis and septic shock are fundamental for emergency clinicians. Optimal sepsis management includes prompt identification of early signs of sepsis and septic shock, hemodynamic optimization, knowledge of clinical and laboratory indicators of subtle and overt organ dysfunction, and prompt infection source identification and control. This structured review summarizes and evaluates the most recent literature on the management of sepsis, focusing on the current evidence, guidelines, and protocols.

Case Presentations

- Her initial vital signs on ED triage are: temperature, 38.5°C; heart rate, 120 beats/min; blood pressure, 135/82 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 95% on room air.

- She is speaking in full sentences, demonstrating normal mentation, and is not in respiratory distress. Her lungs are clear to auscultation. Her abdomen is soft and minimally tender over the suprapubic region without rebound or guarding, with right costovertebral angle tenderness. She has brisk capillary refill. The patient has no recent hospitalizations.

- You believe she looks clinically well, but you wonder how concerned you should be about sepsis…

- His initial vital signs are: temperature, 38.5°C; heart rate, 112 beats/min; blood pressure, 102/68 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 93% on room air.

- He is alert, but thinks it is 1997 and that Bill Clinton is the United States president. Physical examination reveals rales at the left lung base, no wheezing or respiratory distress, tachycardia, a benign abdomen, and well-healing surgical incisions.

- Laboratory findings include WBC of 14 ×103/mm3 with 5% bandemia, platelet count of 130 ×103/mm3, creatinine of 1.5 mg/dL (baseline of 0.85 mg/dL), and serum lactate of 2.5 mmol/L.

- Chest radiograph confirms left lower lobe infiltrate. After receiving ibuprofen and acetaminophen, the patient feels much better and requests to be discharged. His confusion has now resolved; he is oriented to person, place, time, and situation. The nurse asks whether she can remove the IV for the patient to be discharged, but something worries you…

- The paramedics report that he frequently presents for poorly controlled diabetes. He continues to complain of “20/10” pain despite 150 mcg of prehospital IV fentanyl. Prehospital vital signs include: temperature, 39.4°C; heart rate, 135 beats/min; blood pressure, 82/52 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 30 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 88% on room air. His initial glucose level is 342 mg/dL.

- The patient is alert and oriented but screaming in pain as he is transferred from the EMS stretcher. Physical examination reveals tachycardia; delayed capillary refill to 4 seconds; tachypnea; clear breath sounds; and erythema, swelling, and crepitus overlying the right axilla and chest wall.

- After 2 liters of isotonic crystalloid administration by EMS, repeat blood pressure is 70/45 mm Hg. You consider the best antibiotic(s) and are uncertain whether you should initiate vasopressors now, attempt another fluid bolus, or do both simultaneously…

How would you manage these patients? Subscribe for evidence-based best practices and to discover the outcomes.

Clinical Pathway for Initial Emergency Department Management of Patients With Sepsis

Subscribe to access the complete Clinical Pathway to guide your clinical decision making.

Tables

Subscribe for full access to all Tables.

Key References

Following are the most informative references cited in this paper, as determined by the authors.

1. * Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810. (Consensus guidelines) DOI: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287

2. * Meyer NJ, Prescott HC. Sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(22):2133-2146. (Review) DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra2403213

5. * Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(3):304-377. (Policy) DOI: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6

6. * Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Executive summary: Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for the management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(11):1974-1982. (Guidelines) DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005357

11. * Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, et al. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: for the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):775-787. (Review) DOI: 10.1001/jama.2016.0289

15. * Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1589-1596. (Retrospective; 2154 patients) DOI: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9

19. * Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis: for the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):762-774. (Retrospective; 706,399 patients) DOI: 10.1001/jama.2016.0288

61. * National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Early Treatment of Acute Lung Injury Clinical Trials Network, Shapiro NI, Douglas IS, et al. Early restrictive or liberal fluid management for sepsis-induced hypotension. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(6):499-510. (Randomized controlled trial; 1563 patients) DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2212663

81. * De Backer D, Aldecoa C, Njimi H, et al. Dopamine versus norepinephrine in the treatment of septic shock: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):725-730. (Meta-analysis; 11 trials, 2768 patients) DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823778ee

107. * Rhee C, Strich JR, Chiotos K, et al. Improving sepsis outcomes in the era of pay-for-performance and electronic quality measures: a joint IDSA/ACEP/PIDS/SHEA/SHM/SIDP position paper. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;78(3):505-513. (Review) DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciad447

Subscribe to get the full list of 121 references and see how the authors distilled all of the evidence into a concise, clinically relevant, practical resource.

Keywords: shock, hypotension, SOFA, CMS, SEP-1, antibiotic, IV, fluid, lactate, vasopressor, norepinephrine, corticosteroid, bundle