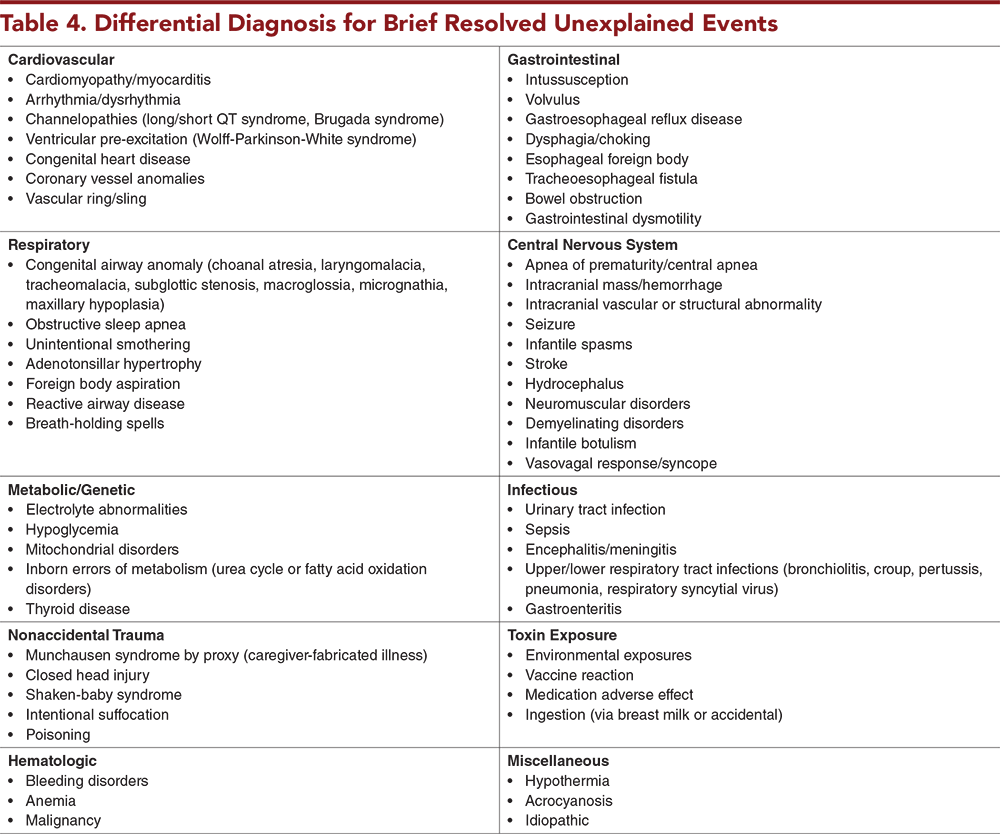

In a 2016 clinical practice guideline, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) created and introduced the term brief resolved unexplained event (BRUE). This guideline defined specific criteria for diagnosis of BRUE and provided a set of guidelines for evaluation of these infants as well as characteristics that indicate a BRUE will have a low risk for a repeat event or a serious underlying disorder. This issue reviews the definition and broad differential diagnosis of a BRUE, highlights the criteria for risk stratification of infants who experience a BRUE, summarizes the management recommendations for patients with a lower-risk BRUE, and examines the available literature that evaluates the impact of the AAP guidelines in the years since its publication.

How would you manage these patients? Subscribe for evidence-based best practices and to discover the outcomes.

![]()

![]() 1. “I ordered basic labs just to be sure this patient with a lower-risk BRUE did not have a serious underlying diagnosis.” Ordering “basic labs” in a lower-risk infant “just to be sure” can be misleading and potentially lead to unnecessary admissions or further testing. Instead, consider obtaining only an ECG and/or pertussis testing if appropriate, and keeping the patient for a brief period of monitoring in the ED.

1. “I ordered basic labs just to be sure this patient with a lower-risk BRUE did not have a serious underlying diagnosis.” Ordering “basic labs” in a lower-risk infant “just to be sure” can be misleading and potentially lead to unnecessary admissions or further testing. Instead, consider obtaining only an ECG and/or pertussis testing if appropriate, and keeping the patient for a brief period of monitoring in the ED.

7. “The triage nurse noted a heart rate of 200 beats/min when the 3-month-old checked in, but it was probably because the baby was crying. It was down to 185 beats/min, and the rest of the history and examination were normal. Since this was a low-risk BRUE, I sent the patient home.” This patient’s vital signs were abnormal on arrival to the ED and their elevated heart rate persisted, but they were still diagnosed with BRUE and discharged. The persistent vital sign abnormality precluded this event from being deemed “resolved,” and this was therefore not a BRUE.

9. “This infant met all the criteria for a lower-risk BRUE and had a normal ECG in the ED. I decided to refer them to cardiology for an outpatient echocardiogram; you can never be too careful with an infant this young!” Lower-risk infants without any cardiac risk factors (eg, family history of sudden death), a normal physical examination, and normal ECG should not be referred for further cardiac testing, as this is unlikely to be of significant diagnostic yield.

Subscribe to access the complete Risk Management Pitfalls to guide your clinical decision making.

Subscribe for full access to all Tables and Figures.

Following are the most informative references cited in this paper, as determined by the authors.

1. * Tieder JS, Bonkowsky JL, Etzel RA, et al. Brief resolved unexplained events (formerly apparent life-threatening events) and evaluation of lower-risk infants. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20160590. (Clinical practice guideline) DOI: 10.1542/peds.2016-0590

6. * Ramgopal S, Soung J, Pitetti RD. Brief resolved unexplained events: analysis of an apparent life threatening event database. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(8):963-968. (Secondary analysis of prospective cohort study; 762 patients) DOI: 10.1016/j.acap.2019.08.001

8. * Bochner R, Tieder JS, Sullivan E, et al. Explanatory diagnoses following hospitalization for a brief resolved unexplained event. Pediatrics. 2021;148(5):e2021052673. (Multicenter retrospective cohort study; 980 patients) DOI: 10.1542/peds.2021-052673

16. * Duncan DR, Liu E, Growdon AS, et al. A prospective study of brief resolved unexplained events: risk factors for persistent symptoms. Hosp Pediatr. 2022;12(12):1030-1043. (Prospective longitudinal cohort study; 124 patients) DOI: 10.1542/hpeds.2022-006550

19. * Brand DA, Fazzari MJ. Risk of death in infants who have experienced a brief resolved unexplained event: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr. 2018;197:63-67. (Meta-analysis and systematic review; 12 studies) DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.12.028

20. * Tieder JS, Sullivan E, Stephans A, et al. Risk factors and outcomes after a brief resolved unexplained event: a multicenter study. Pediatrics. 2021;148(1):e2020036095. (Multicenter retrospective cohort study; 2036 patients) DOI: 10.1542/peds.2020-036095

21. * Nama N, Hall M, Neuman M, et al. Risk prediction after a brief resolved unexplained event. Hosp Pediatr. 2022;12(9):772-785. (Multicenter retrospective cohort study with clinical prediction model derivation; 3283 patients) DOI: 10.1542/hpeds.2022-006637

22. * Mittal MK, Tieder JS, Westphal K, et al. Diagnostic testing for evaluation of brief resolved unexplained events. Acad Emerg Med. 2023;30(6):662-670. (Multicenter retrospective cohort study secondary analysis; 2036 patients) DOI: 10.1111/acem.14666

23. * Patra KP, Hall M, DeLaroche AM, et al. Impact of the AAP guideline on management of brief resolved unexplained events. Hosp Pediatr. 2022;12(9):780-791. (Retrospective observational cohort study; 27,941 encounters) DOI: 10.1542/hpeds.2021-006427

42. * Merritt JL, Quinonez RA, Bonkowsky JL, et al. A framework for evaluation of the higher-risk infant after a brief resolved unexplained event. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2):e20184101. (Clinical practice guideline) DOI: 10.1542/peds.2018-4101

Subscribe to get the full list of 42 references and see how the authors distilled all of the evidence into a concise, clinically relevant, practical resource.

Keywords: brief resolved unexplained event, BRUE, apparent life-threatening event, ALTE, risk stratification, key action statements, lower-risk BRUE, TEN-4-FACESp, cardiopulmonary assessment, nonaccidental trauma, nonaccidental trauma assessment, neurologic assessment, infectious disease assessment, gastrointestinal assessment, inborn errors of metabolism assessment, anemia assessment, family-centered care, patient-centered care, higher-risk patients, high-risk diagnoses

Lukas R. Austin-Page, MD, FAAP; Christine S. Cho, MD, MPH, MEd

Kathleen Berg, MD, FAAEM, FACEP; Nicole Gerber, MD

April 1, 2024

April 1, 2027 CME Information

4 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™, 4 ACEP Category I Credits, 4 AAP Prescribed Credits, 4 AOA Category 2-B Credits.