Table of Contents

About This Issue

Pediatric patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) commonly present to the emergency department for a variety of associated complications, and prompt recognition with appropriate care is imperative. This issue provides an overview of SCD and offers recommendations for the management of the most common complications of SCD seen in pediatric patients. In this issue, you will learn:

Common genotypes of SCD and associated disease severity

Acute and chronic complications observed in patients with SCD

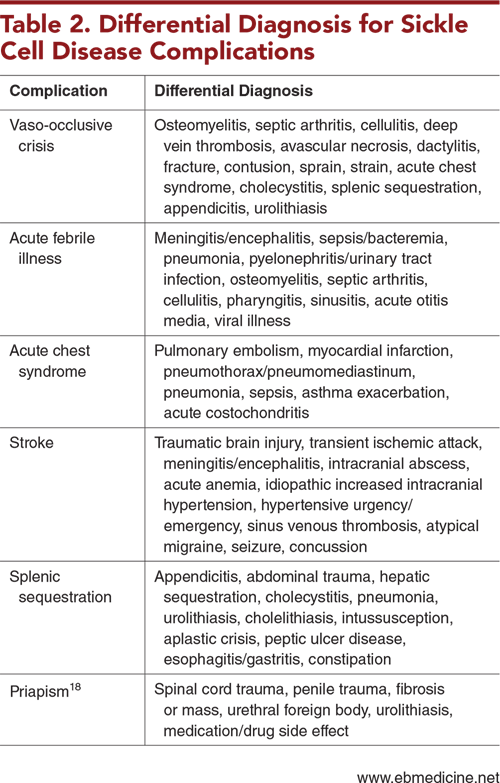

Conditions in the differential diagnosis of complications of SCD

Recommendations for prehospital care of patients with SCD, based on the National Emergency Medical Services clinical guidelines

Key questions to ask when obtaining the history

Components of the physical examination that should be performed for all patients with SCD

Which studies should be considered, based on the severity of symptoms and diagnosis

Recommendations for treatment of common SCD complications, including vaso-occlusive crisis, acute febrile illness, acute chest syndrome, stroke, splenic sequestration, and priapism

Special considerations for patients with SCD and those with sickle cell trait

- About This Issue

- Abstract

- Case Presentations

- Introduction

- Critical Appraisal of the Literature

- Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Vaso-Occlusive Crisis

- Acute Febrile Illness

- Acute Chest Syndrome

- Stroke

- Splenic Sequestration

- Differential Diagnosis

- Prehospital Care

- Emergency Department Evaluation

- History

- Physical Examination

- Diagnostic Studies

- Vaso-Occlusive Crisis

- Acute Febrile Illness

- Acute Chest Syndrome

- Stroke

- Splenic Sequestration

- Priapism

- Treatment

- Vaso-Occlusive Crisis

- Acetaminophen and Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

- Opioids

- Individualized Pain Plans

- Ketamine

- Fluid Administration

- Acute Febrile Illness

- Empiric Antibiotic Therapy

- Hospitalization

- Acute Chest Syndrome

- Stroke

- Splenic Sequestration

- Priapism

- Special Populations

- Patients With Sickle Cell Disease

- Unvaccinated Children

- Children With Human Parvovirus B19 Infection

- Pregnant Patients

- Patients With Pain and High Emergency Department Utilization

- Patients With Sickle Cell Trait

- Exertional Rhabdomyolysis, Cardiovascular Collapse, and Sudden Death

- Hematuria

- Controversies and Cutting Edge

- Disposition

- Summary

- Time- and Cost-Effective Strategies

- 5 Things That Will Change Your Practice

- Risk Management Pitfalls in Managing Pediatric Patients With Sickle Cell Disease

- Case Conclusions

- Clinical Pathways

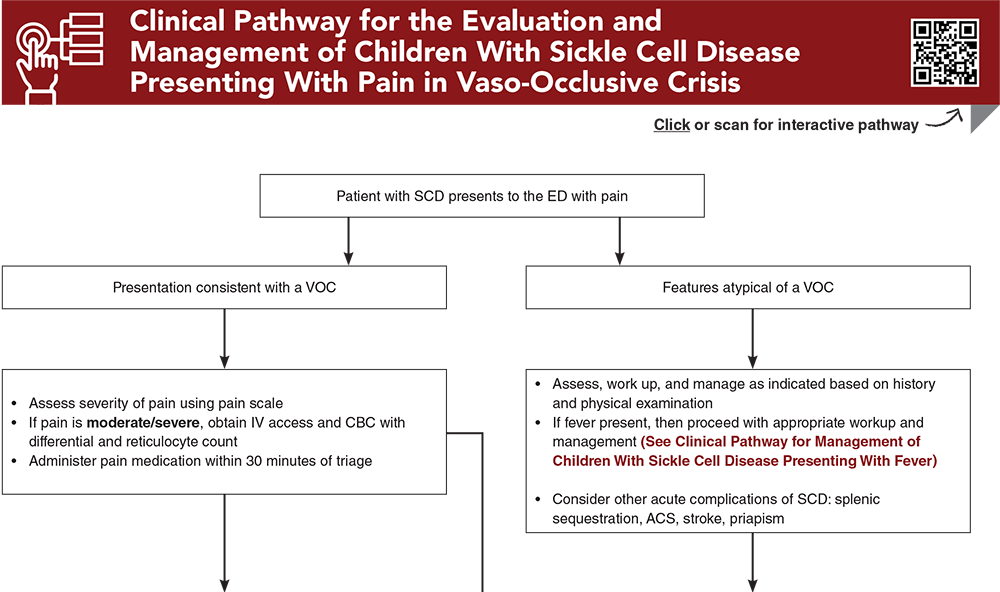

- Clinical Pathway for the Evaluation and Management of Children With Sickle Cell Disease Presenting With Pain in Vaso-Occlusive Crisis

- Clinical Pathway for the Evaluation and Management of Children With Sickle Cell Disease Presenting With Fever

- Tables and Figures

- References

Abstract

The complications of sickle cell disease (SCD) in pediatric patients are some of the more common chronic conditions that present to the emergency department. It is important that emergency clinicians understand the features of SCD, its related complications, and the associated diagnostic and therapeutic modalities to provide this patient population with the most evidenced-based and high-quality care. This review describes the acute complications and evidence-based emergent management of SCD in pediatric patients.

Case Presentations

- The boy’s symptoms have progressed over 2 days, with a temperature of 38.9°C starting 1 hour ago.

- The boy’s vital signs are: heart rate, 120 beats/min; respiratory rate, 29 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 88% on room air. Auscultation reveals decreased breath sounds in the right lower lobe. Chest x-ray shows a right lower lobe infiltrate. You place the boy on nasal cannula for oxygen support.

- What is the differential diagnosis? How should you manage this patient?

- The girl is lying on her mother‘s lap. Her vital signs are: heart rate, 159 beats/min; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 98% on room air.

- On examination, she has a distended abdomen and a palpable splenic edge.

- What is the most concerning diagnosis for this patient?

- On examination, the boy has normal vital signs and appears to be in pain. He reports moderate pain when his right shoulder and thighs are palpated. He tried ibuprofen and hydrocodone-acetaminophen at home, without improvement. No other known trauma is reported.

- What is the differential diagnosis? How should you manage this patient?

How would you manage these patients? Subscribe for evidence-based best practices and to discover the outcomes.

Clinical Pathway for the Evaluation and Management of Children With Sickle Cell Disease Presenting With Pain in Vaso-Occlusive Crisis

Subscribe to access the complete Clinical Pathway to guide your clinical decision making.

Tables and Figures

Subscribe for full access to all Tables and Figures.

Buy this issue and

CME test to get 4 CME credits.

Key References

Following are the most informative references cited in this paper, as determined by the authors.

1. * Piel FB, Rees DC, DeBaun MR, et al. Defining global strategies to improve outcomes in sickle cell disease: a Lancet Haematology Commission. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10(8):e633-e686. (Evidence-based expert panel report) DOI: 10.1016/S2352-3026(23)00096-0

2. * United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data & statistics on sickle cell disease. Accessed October 1, 2024. (CDC data)

4. * United States Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Evidence-based management of sickle cell disease. 2014. (Expert panel report)

5. * Brandow AM, Carroll CP, Creary S, et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: management of acute and chronic pain. Blood Adv. 2020;4(12):2656-2701. (Society guidelines) DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001851

6. * Kavanagh PL, Hirshon JM. EDSC3: working to improve emergency department care of individuals with sickle cell disease. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(3S):S80-S82. (Review) DOI: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.08.016

52. * DeBaun MR, Jordan LC, King AA, et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cerebrovascular disease in children and adults. Blood Adv. 2020;4(8):1554-1588. (Expert panel review guidelines) DOI: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.427

Subscribe to get the full list of 103 references and see how the authors distilled all of the evidence into a concise, clinically relevant, practical resource.

Keywords: pediatric sickle cell, sickle cell disease, SCD, hemoglobin, vaso-occlusive crisis, acute febrile illness, splenic sequestration, acute chest syndrome, ACS, stroke, dactylitis, priapism, sickle cell trait, SCT, ECAST, exercise collapse, hematuria, renal papillary necrosis, renal medullary carcinoma, exertional rhabdomyolysis